Conservation of Wild Food Plants and Their Potential for Combatting Food Insecurity in Kenya as Exemplified by the Drylands of Kitui County

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Study Area

1.2. Food Plants of Kitui County

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Diversity of Edible Plants

2.2. Growth Habit

2.3. Plant Parts Used

2.4. Food Types Obtained from Wild Edible Plants

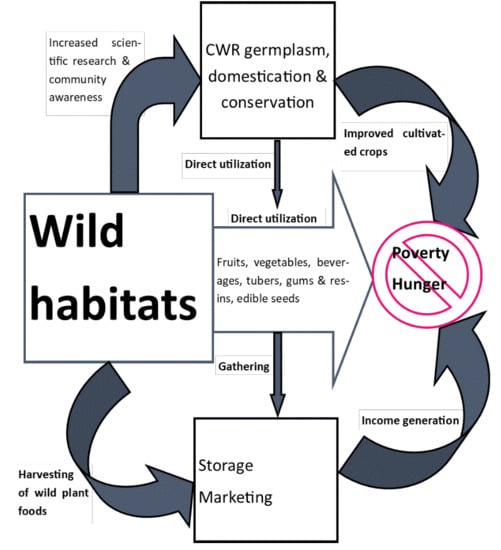

2.5. Potential of Crop Wild Relatives (CWR) in Kitui County

2.6. Conservation of Natural Habitats in Kitui County

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kigomo, N.B. State of Forest genetic Resources in Kenya. In Forest Genetic Resources Working Papers, Proceedings of the Sub-Regional Workshop FAO/IPGRI/ICRAF on the Conservation, Management, Sustainable Utilisation and Enhancement of Forest Genetic Resources in Sahelian and North-Sudanian Africa; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2001; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen, S.; Lind, J. Adaptation as a political process: Adjusting to drought and conflict in Kenya’s drylands. Environ. Manag. 2009, 43, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boko, M.; Niang, I.; Nyong, A.; Vogel, C.; Githeko, A.; Medany, M.; Osman-Elasha, B.; Tabo, R.; Yanda, P. Africa. In Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Parry, M.L., Canziani, O.F., Palutikof, J.P., van der Linden, P.J., Hanson, C.E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 433–467. [Google Scholar]

- Hulme, M.; Doherty, R.; Ngara, T.; New, M.; Lister, D. African climate change: 1900–2100. Clim. Res. 2001, 17, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Owuor, B.; Eriksen, S.; Mauta, W. Adapting to climate change in a dryland mountain environment in Kenya. Mt. Res. Dev. 2005, 25, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scoones, I. Hazards and Opportunities: Farming Livelihoods in Dryland Africa. Lessons from Zimbabwe; Zed Books: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gachathi, F.N.; Eriksen, S. Gums and resins: The potential for supporting sustainable adaptation in Kenya’s drylands. Clim. Dev. 2011, 3, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellema, W.; Mujawamariya, G.; D’Haese, M. Gum arabic collection in northern Kenya: Unexploited resources, underdeveloped markets. Afr. Focus 2014, 27, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johns, T.; Kokwaro, J.O. Food plants of the Luo of Siaya District, Kenya. Econ. Bot. 1991, 45, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maundu, P. Utilization and conservation status of wild food plants in Kenya. In Biodiversity of African Plants; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996; pp. 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinyuru, J.N.; Konyole, S.O.; Kenji, G.M.; Onyango, C.A.; Owino, V.O.; Owuor, B.O.; Estambale, B.B.; Friis, H.; Roos, N. Identification of traditional foods with public health potential for complementary feeding in Western Kenya. J. Food Res. 2012, 1, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nyambo, A.; Nyomora, A.; Ruffo, C.; Tengnas, B. Fruits and Nuts: Species with Potential for Tanzania; World Agroforestry Centre, Eastern and Central Africa Regional Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mbora, A.; Jamnadass, R.; Lillesø, J.B. Growing High Priority Fruits and Nuts in Kenya: Uses and Management; World Agroforestry Centre: Nairobi, Kenya, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa, M. The Utilization of Wild Food Plants by the Suiei Dorobo in Northern Kenya. J. Anthropol. Soc. Nippon 1980, 88, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kariuki, L.; Maundu, P.; Morimoto, Y. Some intervention strategies for promoting underutilized species: Case of local vegetables in Kitui District, Kenya. II International Symposium on Underutilized Plant Species: Crops for the Future-Beyond Food Security; International Society for Horticultural Science: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeno, J.A.; Chebet, D.K.; Mathenge, P.W. Status of indigenous vegetable utilization in Kenya. In XXVI International Horticultural Congress: Horticultural Science in Emerging Economies, Issues and Constraints; ISHS: Leuven, Belgium, 2002; Volume 621, pp. 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, B.; Mbuni, Y.; Yan, X.; Mwachala, G. Vascular flora of Kenya based on the Flora of Tropical East Africa. PhytoKeys 2017, 126, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gachathi, F.N. A vital habitat to local livelihood and drought coping strategies in the drylands: The case of Endau Hilltop forest, Kitui District, Kenya. In Proceedings of the Two Workshops; Eriksen, S., Owuor, B., Nyukuri, E., Eds.; World Agroforestry Centre: Nairobi, Kenya; KEFRI Research Centre: Kitui, Kenya, 2005; pp. 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa, M. A Preliminary Report on the Ethnobotany of the Suiei Dorobo in Northern Kenya. Afr. Study Monogr. 1987, 7, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabuye, C.H. Edible roots from wild plants in arid and semi-arid Kenya. J. Arid Environ. 1986, 11, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, F. Agriculture and use of wild and weedy greens by the Piik AP Oom Okiek of Kenya. Econ. Bot. 2001, 55, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajat, J.; Jefwa, J.; Mwafaida, J. Survey on Indigenous Food Plants of Kaya Kauma and Kaya Tsolokero in Kilifi County Kenya. J. Life Sci. 2017, 11, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Njoroge, G.N.; Kaibui, I.M.; Njenga, P.K.; Odhiambo, P.O. Utilization of priority traditional medicinal plants and local people’s knowledge on their conservation status in arid lands of Kenya (Mwingi District). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2010, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kisangau, D.P.; Kauti, M.; Mwobobia, R.; Kanui, T.; Musimba, N. Traditional Knowledge on Use of Medicinal Plants in Kitui County, Kenya. Int. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2017, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mutie, F.M.; Gao, L.-L.; Kathambi, V.; Rono, P.C.; Musili, P.M.; Ngugi, G.; Hu, G.-W.; Wang, Q.-F. An Ethnobotanical Survey of a Dryland Botanical Garden and Its Environs in Kenya: The Mutomo Hill Plant Sanctuary. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dundas, C. History of Kitui. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. G. B. Irel. 1913, 43, 480–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- County, G.K. County Integrated Development Plan 2013–2017: Planning for Sustainable Socio-Economic Growth and Development; County Government of Kitui: Kitui, Kenya, 2014; p. 600.

- Bélair, C.; Ichikawa, K.; Wong, B.Y.L.; Mulongoy, K.J. (Eds.) Sustainable Use of Biological Diversity in Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes, Background to the ‘Satoyama Initiative for the Benefit of Biodiversity and Human Well-Being’; Technical Series; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2010; pp. 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Saggerson, E.P. Geology of the South Kitui Area: Degree Sheet 53, SW Quarter, with Colored Geological Map; Geological Survey of Kenya: Nairobi, Kenya, 1957; Volume 37. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, O.M.; Malombe, I.; Davis, S.D.; Pearce, T.; Simmonds, M. Identifying priority species in dryland Kenya for conservation in the Millennium Seed Bank Project. In Proceedings of the Systematics and Conservation of African Plants; Royal Botanic Gardens: London, UK, 2010; pp. 749–758. [Google Scholar]

- Lind, E.M.; Morrison, M.E.; Hamilton, A. East African Vegetation; Longman Group Limited: London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Malonza, P.K.; Muasya, A.M.; Lange, C.; Webala, P.; Mulwa, R.K.; Wasonga, D.V.; Mwachala, G.; Malombe, I.; Muasya, J.; Kirika, P.; et al. Biodiversity Assessment in Dryland Hilltops of Kitui and Mwingi Districts; National Museums of Kenya: Nairobi, Kenya, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tignor, R.L. Kamba political protest: The destocking controversy of 1938. Afr. Hist. Stud. 1971, 4, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanner, W. The Kitui Kamba Market, 1938–1939. Ethnology 1969, 8, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duodu, K.G.; Apea-Bah, F.B. African legumes: Nutritional and health-promoting attributes. In Gluten-Free Ancient Grains; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 223–269. [Google Scholar]

- Maundu, M.; Ngugi, W.; Kabuye, H. Traditional Food Plants of Kenya; National Museums of Kenya: Nairobi, Kenya, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa, M.; Kimura, D.; Terashima, H. AFlora: A database of traditional plant use in tropical Africa. Syst. Geogr. Plants 2001, 71, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chretin, M.; Chikamai, B.; Loktari, P.E.; Ngichili, J.; Loupa, N.; Odee, D.; Lesueur, D. The current situation and prospects for gum Arabic in Kenya: A promising sector for pastoralists living in arid lands. Int. For. Rev. 2008, 10, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beentje, H.; Adamson, J.; Bhanderi, D. Kenya Trees, Shrubs, and Lianas; National Museums of Kenya: Nairobi, Kenya, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wyk, B.-E.; Gorelik, B. The history and ethnobotany of Cape herbal teas. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 170, 13–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, M. Speciality and herbal teas. In Tea; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1992; pp. 513–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne-Redhead, E.; Turrill, W.B. (Eds.) Flora of Tropical East Africa; Crown Agents: London, UK, 1974; pp. 1952–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew, A.D.Q. Upland Kenya Wild Flowers and Ferns: A Flora of the Flowers, Ferns, Grasses, and Sedges of Highland Kenya; Nature Kenya-The East Africa Natural History Society: Nairobi, Kenya, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Muthee, J.K.; Gakuya, D.W.; Mbaria, J.M.; Kareru, P.G.; Mulei, C.M.; Njonge, F.K. Ethnobotanical study of anthelmintic and other medicinal plants traditionally used in Loitoktok District of Kenya. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 135, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinnaird, F. Competition for a forest palm: Use of Phoenix reclinata by human and nonhuman primates. Conserv. Biol. 1992, 6, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muok, B.O.; Owuor, B.; Dawson, I.; Were, J. The potential of indigenous fruit trees: Results of a survey in Kitui District, Kenya. Agrofor. Today 2000, 12, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Simitu, P.J. Consumption and Conservation of Drylands’ Indigenous Fruit Trees for Rural Livelihood Improvement in Mwingi District, Kenya. Master’s Thesis, Kenyatta University, Kenya Drive, Nairobi, Kenya, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, I.; Gachathi, F. A check list of the plant species at the site of the Kenya and Japan Social Forestry Training Project, Kitui, Kenya. Veg. Sci. 1998, 15, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikamai, B.; Gachathi, F.N. Gum and Resin Resources in Isiolo District, Kenya: Ethnobotanical and Reconnaissance Survey. East Afr. Agric. For. J. 1994, 59, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polhill, R.M. Miscellaneous notes on African species of Crotalaria, L.: II. Kew Bull. 1968, 22, 169–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wambugu, P.W.; Muthamia, Z.K. Country report on the state of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture: Kenya. In The Second Report on the State of the World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Bally, P.R.O. The Mutomo hill plant sanctuary, Kenya. Biol. Conserv. 1968, 1, 90–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdcourt, B. An enumeration of the Rhamnaceae in the East African Herbarium with the description of a new species of Lasiodiscus. Bull. du Jard. Bot. l’État a Bruxelles 1957, 27, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; Berardi, A. Savannas and Dry Forests: Linking People with Nature; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tanksley, S.D.; McCouch, S.R. Seed banks and molecular maps: Unlocking genetic potential from the wild. Science 1997, 277, 1063–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maxted, N.; Ford-Lloyd, B.V.; Jury, S.; Kell, S.; Scholten, M. Towards a definition of a crop wild relative. Biodivers. Conserv. 2006, 15, 2673–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeno, J.A.; Mutegi, E.; de Villiers, S.; Wolt, J.D.; Misra, M.K. Morphological Variation in the Wild-Weedy Complex of Sorghum bicolor In Situ in Western Kenya: Preliminary Evidence of Crop-to-Wild Gene Flow? Int. J. Plant Sci. 2012, 173, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maxted, N.; Brehm, J.M.; Kell, S. Resource Book for the Preparation of National Plans for Conservation of Crop Wild Relatives and Landraces; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013; p. 463. [Google Scholar]

- Labeyrie, V.; Rono, B.; Leclerc, C. How social organization shapes crop diversity: An ecological anthropology approach among Tharaka farmers of Mount Kenya. Agric. Hum. Values 2013, 31, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxted, N.; Scholten, M.; Codd, R.; Ford-Lloyd, B. Creation and use of a national inventory of crop wild relatives. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 140, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, F.E.M. Economic Botany Data Collection Standard; Royal Botanic Gardens: London, UK, 1995; p. 146. [Google Scholar]

| Family | Genus | Species | Family | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leguminosae | 13 | 25 | Convolvulaceae | 1 | 2 |

| Malvaceae | 6 | 17 | Ebenaceae | 2 | 2 |

| Rubiaceae | 6 | 11 | Euphorbiaceae | 2 | 2 |

| Anacardiaceae | 3 | 10 | Poaceae | 1 | 2 |

| Cucurbitaceae | 7 | 9 | Portulacaceae | 1 | 2 |

| Lamiaceae | 4 | 9 | Salvadoraceae | 2 | 2 |

| Burseraceae | 2 | 7 | Bignoniaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Moraceae | 2 | 7 | Campanulaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Amaranthaceae | 3 | 6 | Cannabaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Capparaceae | 3 | 6 | Cleomaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Rhamnaceae | 3 | 6 | Clusiaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Apocynaceae | 5 | 5 | Combretaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Rutaceae | 3 | 5 | Menispermaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Verbenaceae | 2 | 5 | Nymphaeaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Zygophyllaceae | 1 | 5 | Olacaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Annonaceae | 2 | 4 | Opiliaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Phyllanthaceae | 3 | 4 | Pedaliaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Boraginaceae | 1 | 3 | Polygonaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Commelinaceae | 1 | 3 | Salicaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Compositae | 3 | 3 | Santalaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Cyperaceae | 2 | 3 | Sapotaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Loganiaceae | 1 | 3 | Solanaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Oleaceae | 2 | 3 | Xanthorrhoeaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Sapindaceae | 3 | 3 | Geraniaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Vitaceae | 2 | 3 | Putranjivaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Arecaceae | 2 | 2 | Talinaceae | 1 | 1 |

| Food Types | Number of Species | Specific Food Type | Number of Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fruits | 120 | Eaten raw | 119 |

| Cooked | 1 | ||

| Vegetables | 44 | Green vegetables | 43 |

| Tuber vegetables | 1 | ||

| Beverages | 28 | Tisanes | 22 |

| Beers | 4 | ||

| Wines | 1 | ||

| Coffee substitutes | 1 | ||

| Food additives | 22 | Flavoring agents | 17 |

| Sweeteners | 2 | ||

| Fermenting agents | 2 | ||

| Water clarifiers | 2 | ||

| Milk curdlers | 1 | ||

| Meat tenderizers | 2 | ||

| Starch foods | 21 | Tubers | 21 |

| Seed foods | 22 | Other seeds | 13 |

| Pulses | 5 | ||

| Cereals | 2 | ||

| Pseudo-cereals | 2 | ||

| Gums and resins | 13 | Eaten raw | 13 |

| Others | 24 | Leaves chewed raw | 8 |

| Barks chewed raw | 7 | ||

| Roots chewed raw | 4 | ||

| Inflorescence eaten raw | 5 | ||

| Edible cotyledon/embryo | 3 | ||

| Internal juice of fruit drunk | 1 | ||

| Galls | 1 | ||

| Stem pith chewed raw | 1 |

| Family and Plant Species | Kamba Name | Growth Habit | Presence in Kitui County | Part Used; Use in Kenya | Source of Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amaranthaceae | |||||

| #Amaranthus dubius Mart. ex Thell. | W’oa, telele, terere | Herb | Lind and Agnew 5642 (EA) | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [15,36] |

| Amaranthus graecizans L. | W’oa, telele, terere | Herb | Gilbert 70 (EA) | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [36] |

| Amaranthus hybridus L. | W’oa, telele, terere | Herb | Gilbert 98 (EA) | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [21,36,42] |

| Amaranthus spinosus L. | Herb | Gilbert 97 (EA) | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [36] | |

| Digera muricata (L.) Mart. | Walange | Herb | Someren 2024 (EA) | Leaves, flowers; leaves eaten as a vegetable. Flower nectar is edible. | [36] |

| * Aerva lanata (L.) Juss. | _ | Herb | SAJIT-Mutie MU0268 (EA) | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [36] |

| Anacardiaceae | |||||

| #Lannea alata (Engl.) Engl. | Kitungu, ndungu, mukolya | Shrub or tree | Kuchar 14876 (EA) | Fruits, bark; ripe fruits edible. Bark used in tea. | [18,36,39] |

| * Lannea schweinfurthii Engl. | Muasi, kyuasi | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0271 (EA) | Fruits, bark; ripe fruits edible. Bark used for making tea. | [18,39] |

| #Lannea triphylla (Hochst. ex A. Rich.) Engl. | Muthaalwa, kithaalwa, kithaala, nzaala | Shrub or tree | [36] | Fruits, bark, root; ripe fruits are edible. Sweet succulent roots and bark chewed raw to quench thirst. Bark used in tea. | [18,19,20,36,39] |

| #Searsia natalensis (Bernh. ex C.Krauss) F.A.Barkley | Kitheu, mutheu | Shrub or tree | Evans 167 (EA) | Fruits, bark, roots, leaves; ripe fruits are edible. Bark used in tea. Roots boiled in soup. Young shoots chewed raw. | [18,36,39] |

| * Lannea rivae Sacleux | Kithaalwa, muthaalwa, kithaala, kithaalua kya kiima | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0305 (EA, HIB) | Fruits, bark; ripe fruits are edible. Bark is sweet and chewed raw. | [36,39] |

| Lannea schimperi (Hochst. ex A.Rich.) Engl. | kithoona, kithauna, nthoona | Shrub or tree | [36] | Fruits, bark; ripe fruits are edible. Bark used in tea. | [36] |

| Searsia tenuinervis (Engl.) Moffett | Kitheu | Shrub or tree | [36] | Fruits, leaves; ripe fruits are edible. Young shoots and leaves chewed raw. | [36,39] |

| Searsia quartiniana (A.Rich.) A.J.Mill. | Mutheu | Shrub or tree | [36] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18,36] |

| Searsia pyroides (Burch.) Moffett | Kitheu, mutheu, mutheu munene | Shrub or tree | [36] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [36,39] |

| #Sclerocarya birrea (A.Rich.) Hochst. | Muua, muuw’a, mauw’a | Tree | Bogdan AB4379 (EA) | Fruits, seeds; ripe fruits are edible. Internal seed contents eaten raw. | [18,36,39,46] |

| Annonaceae | |||||

| #* Uvaria scheffleri Diels | Mukukuma | Shrub or liana | SAJIT-Mutie MU0290 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18,19,36,39] |

| #Annona senegalensis Pers. | Makulo, mutomoko ‘wild custard apple, wild soursop’ | Shrub or tree | [36] | Bark, fruits; ripe fruits are edible. Bark chewed raw. | [39,47] |

| #Uvaria acuminata Oliv. | _ | Shrub or liana | Mwachala et al., 476 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [36,39] |

| Uvaria lucida Bojer ex Benth. | _ | Shrub or liana | Mbonge 14 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [36] |

| Apocynaceae | |||||

| * Saba comorensis (Bojer ex A.DC.) Pichon | Kilia, kiongwa, kyongoa, mongoa | Liana | SAJIT-Mutie MU0278 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [22,36,39] |

| * Cynanchum hastifolium K.Schum. | _ | Climber | SAJIT-Mutie MU0261 (EA) | Unripe fruits; edible. | [19] |

| #Carissa spinarum L. | Mukawa, mutote, ngawa, ndote, nzunu | Shrub | [48] | Flowers, fruits, roots; flowers and ripe fruits are edible. Boiled roots eaten as vegetables and used as a flavor in soup. | [18,19,20,36,39,47] |

| Acokanthera schimperi (A.DC.) Schweinf. | Kivai | Shrub or tree | [36] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18,36,39] |

| * Pentarrhinum insipidum E.Mey. | _ | Climber | SAJIT-Mutie MU0139 (EA) | Fruits, leaves; leaves eaten as a vegetable. Ripe fruits are edible. | [20,36] |

| Arecaceae | |||||

| Phoenix reclinata Jacq. | Makindu ‘wild date palm’ | Tree | [36,48] | Fruits, stem; ripe fruits are edible. Wine is tapped from stem. | [36,39] |

| #Hyphaene compressa H.Wendl. | Mukoma, ilala | Tree | [36] | Fruits, leaves; seedling embryo is edible. Fruit pulp eaten raw. Juice from immature fruits drunk fresh or used to make beer. | [36,39,47] |

| Bignoniaceae | |||||

| #Kigelia africana (Lam.) Benth. | Kiatine, muatine ‘sausage tree’ | Shrub or tree | [48] | Fruits; used for fermenting traditional beer. | [18,39] |

| #Cordia monoica Roxb. | Muthii, kithei, nthei | Shrub or tree | [48] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18,19,36,39,47] |

| #* Cordia sinensis Lam. | Muthea, kithea, muthei-munini, kithia | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0292 (EA) | Exudate, roots, fruits; roots eaten raw. Ripe fruits are edible. Fruit pulp used for brewing local beer. Produces an edible gum. | [18,19,36,39] |

| Cordia crenata Delile | _ | Shrub or tree | Kirika et al., GBK2/10/2005 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39] |

| Burseraceae | |||||

| #* Commiphora baluensis Engl. | Itula, mutula | Tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0254 (EA) | Bark; used in making tea. | [18,19,39] |

| * Commiphora edulis (Klotzsch) Engl. | Kyoa kika | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0193 (EA) | Fruits; seed aril from ripe fruit is edible. | [19] |

| #Boswellia neglecta S.Moore | Kinondo | Shrub or tree | Bally B1612 (EA) | Exudate, bark; resin from bark chewed. Bark used for making tea. | [18,36,39,49] |

| Commiphora campestris Engl | _ | Tree | [48] | Exudate; produces an edible resin. | [49] |

| * Commiphora africana (A.Rich.) Endl. | Kitungu, mutungu, itula | Shrub or tree | Kuchar 15067 (EA) | Exudate, roots, bark; produces an edible gum. Roots of young plants chewed raw to quench thirst. Bark used for making tea. | [18,36,39] |

| Commiphora rostrata Engl. | Inywamanzi | Shrub or tree | [48] | Bark, leaves, stem; leaves chewed raw or cooked to add flavor in foods. Bark used for tea. Stem pith and bark of young plants chewed raw to quench thirst. | [18,20,36,39] |

| Commiphora schimperi (O.Bergman) Engl. | Mutungu | Shrub or tree | [36,48] | Exudate, roots, bark; produces an edible resin. Roots chewed to quench thirst. Inner red bark boiled in tea. | [19,36,39] |

| Campanulaceae | |||||

| #Cyphia glandulifera Hochst. ex A.Rich. | Ngomo | Herb | [36] | Roots, leaves; leaves eaten as a vegetable. Tubers eaten raw. | [14,19] |

| Cannabaceae | |||||

| Trema orientalis (L.) Blume | _ | Shrub or tree | [18] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39] |

| Capparaceae | |||||

| #Boscia coriacea Graells | Isivu | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0122 (EA) | Fruits, seeds; fruits are edible. Seeds edible when boiled. | [18,36,39,47] |

| #Maerua decumbens (Brongn.) DeWolf | Kinatha, munatha | Herb or shrub | Kuchar 15244 (EA) | Roots, fruits, seeds; ripe fruits eaten raw or cooked. Seeds edible when boiled. Root bark chewed raw. Roots added to water as a sweetener. | [18,36,39,47] |

| #Maerua denhardtiorum Gilg | Itembokambola | Shrub | Kuchar 14991 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18,19,39,47] |

| Maerua kirkii F. White | Ivovotwe | Shrub or tree | Kimani 86 (EA) | Nuts; boiled and eaten. | [19] |

| Thilachium africanum Lour. | Mutunguu | Shrub or tree | Greenway 9228 (EA) | Roots; cooked and eaten. | [39] |

| Thilachium thomasii Gilg | Kitungulu | Shrub or tree | Spjut and Muchai 4655 (EA) | Roots, fruits; ripe fruits are edible. Tubers eaten or cooked and the resultant liquid drunk or used for making tea. Peeled roots used as flocculants in water. | [36,39] |

| Cleomaceae | |||||

| #Cleome gynandra L. | Mwianzo, mukakai, sake, mwaanzo, ithea-utuku | Herb | Hucks 341 (EA) | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [19,21,36,42] |

| Clusiaceae | |||||

| #Garcinia livingstonei T.Anderson | Mukanga, kikangakanywa, ngangakanywa | Tree | Adamson B6084 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [19,36,39,47] |

| Combretaceae | |||||

| #Terminalia brownii Fresen. | Muuku, kiuku | Shrub or tree | Gillett 19774 (EA) | Fruits; eaten by children. | [18,39,47] |

| Commelinaceae | |||||

| #Commelina africana L. | Kikowe | Herb | [36] | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [20,28,36] |

| Commelina benghalensis L. | Itula | Herb | [36] | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [36] |

| #Commelina forskaolii Vahl | Kikowe, kikoe | Herb | [36] | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [15,36] |

| Compositae | |||||

| * Launaea cornuta (Hochst. ex Oliv. and Hiern) C.Jeffrey | Uthunga, muthunga | Herb | SAJIT-Mutie MU0209 (EA) | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [22,36] |

| Cyanthillium cinereum (L.) H.Rob. | _ | Herb | Kuchar 15163 (EA) | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [36] |

| Galinsoga parviflora Cav. | _ | Herb | Sheldrick TNP/E/109 (EA) | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [36] |

| Convolvulaceae | |||||

| Ipomoea lapathifolia Hallier f. | Nzola, kinzola | Herb | Ossent 441A (EA) | Roots; tubers eaten raw. | [36] |

| Ipomoea mombassana Vatke | Ukwai wa nthi, wimbia, musele, uthui | Climber | Napper 1591 (EA) | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [36] |

| Cucurbitaceae | |||||

| #Momordica spinosa Chiov. | _ | Liana | Kuchar 14829 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39,47] |

| * Coccinia grandis (L.) Voigt | Kimuya, kimowe, imore, imondiu | Climber | SAJIT-Mutie MU0176 (HIB) | Leaves, fruits; leaves eaten as a vegetable. Ripe fruits eaten raw or ground into flour and used to make porridge. | [36] |

| #* Cucumis dipsaceus Ehrenb. ex Spach | Kikungi, kyambatwa | Climber | SAJIT-Mutie MU0145 (HIB) | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [36] |

| * Kedrostis pseudogijef C. Jeffrey | Mukauw’u | Climber | SAJIT-Mutie MU0212 (EA) | Leaves, fruits; leaves eaten as a vegetable. Ripe fruits are edible. | [36] |

| Kedrostis gijef C. Jeffrey | Witulu | Climber | Kuchar 1503 (EA) | Leaves, fruits; leaves eaten as a vegetable. Ripe fruits are edible. | [36] |

| * Momordica rostrata A. Zimm. | Kiongoa, kyongoa | Climber | SAJIT-Mutie MU0149 (HIB) | Leaves, seeds, fruits; ripe fruits are edible. Roasted seeds are edible. Leaves eaten as a vegetable. | [36] |

| #Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. | Ungu, kikuu, yungu | Climber | [36] | Leaves, fruits, seeds; young fruits edible when cooked. Seeds roasted and eaten. Leaves eaten as a vegetable. | [28,36] |

| #Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. and Nakai | Itikitiki | Climber | [28] | Fruits, leaves, seeds; ripe fruits are edible. Dry seeds ground into flour, mixed with sorghum flour and used to make porridge. Leaves eaten as a vegetable. | [28,36] |

| Peponium vogelii | _ | Climber | Kimani 80 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [19] |

| Cyperaceae | |||||

| Cyperus blysmoides Hochst. ex C.B.Clarke | _ | Herb | Edwards 23 (EA) | Roots; bulbs and stem bases eaten raw. | [20,28] |

| Cyperus rotundus L. | _ | Herb | Porter 51 (EA) | Roots; stem bases are edible. | [36] |

| Kyllinga alba | _ | Herb | Kuchar 8848 (EA) | Root bulbs; edible. | [19] |

| Ebenaceae | |||||

| #* Diospyros mespiliformis Hochst. ex A.DC. | Mukongoo ‘African ebony’ | Tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0179 (HIB) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18,36,39,47] |

| Euclea divinorum Hiern | Mukinyai, mukinyai, mukuthi, nginyai | Shrub or tree | Kuchar 15097 (EA) | Fruits, bark; ripe fruits are edible. Bark added to soup as an appetizer. | [18,36,39] |

| Euphorbiaceae | |||||

| #* Croton dichogamus Pax | Mwalula, muthiani | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0245 (EA) | Bark; used as a flavor in soup. | [18,20,39] |

| Euphorbia schefleri Pax | _ | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0188 (HIB) | Stems; smoke from wood used as a meat tenderizer. | [39] |

| Geraniaceae | |||||

| Pelargonium quinquelobatum Hochst. ex Rich. | _ | Herb | Muasya 2459 (EA) | Stems; eaten raw. | [19] |

| Lamiaceae | |||||

| #* Vitex payos (Lour.) Merr. | Kimuu, muu | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0286 (EA, HIB) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [36,39,47] |

| * Vitex strickeri Vatke and Hildebr. | Mwalika | Shrub or liana | SAJIT-Mutie MU0264 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39] |

| * Hoslundia opposita Vahl | Musovi, musovasovi | Shrub | SAJIT-Mutie MU0244 (EA) | Fruits, leaves, stems; ripe fruits are edible. Leaves and stems used in tea. | [19,36,39] |

| Ocimum basilicum L. | Mutaa | Herb | [48] | Leaves; used for flavoring tea. | [18,36] |

| Ocimum kilimandscharicum Gürke | Wenye | Herb or shrub | Brilloe B303 (EA) | Leaves; used for flavoring tea. | [36,39] |

| Ocimum gratissimum L. | Mukandu | Shrub | Mbonge 6 (EA) | Leaves; used for flavoring tea. | [36,39] |

| * Premna oligotricha Baker | Mukaakaa | Shrub | SAJIT-Mutie MU0183 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [19] |

| #Premna resinosa (Hochst.) Schauer | Shrub | Kirika et al., NMK455 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [19,47] | |

| #Vitex doniana Sweet | Kimuu ‘Black plum, vitex’ | Tree | [18] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18,36,39] |

| Leguminosae | |||||

| #* Acacia nilotica (L.) Delile | Musemei, musemeli | Tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0224 (EA) | Bark, fruit; bark and pods boiled with sugar to make tea. Pods eaten during famine. | [18,36,39] |

| Acacia reficiens Wawra | _ | Shrub or tree | Ament and Magogo 418 (EA) | Sweet inner bark; chewed raw. | [19] |

| #* Acacia senegal (L.) Willd. | King’olola | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0122 (HIB) | Exudate; produces an edible gum. | [18,19,36,49] |

| #Acacia seyal Delile | Kinyua, kisewa | Shrub or tree | Robertson 4288 (EA) | Exudate, bark; produces an edible gum. Bark chewed raw or ground into powder to make tea. | [18,36,39,49] |

| Acacia gerrardii Benth. | Munina, kithi, muthii | Shrub or tree | [18] | Bark; used to make soup. | [18,39] |

| Acacia drepanolobium Sjostedt | Kiunga, muuga | Shrub or tree | [36] | Galls, fruits; inner flesh of the galls is edible. Young fruits are edible. | [36,39] |

| Acacia hockii De Wild. | Muuga, kinyua ‘white thorn’ | Shrub or tree | Gardner 1088 (EA) | Exudate, bark; produces an edible gum. Inner bark chewed raw to quench thirst. | [36,39] |

| * Acacia tortilis (Forssk.) Hayne | Mwaa, kilaa, mulaa, muaa, ulaa | Tree | Sangai 935 (EA) | Exudate, fruits; produces an edible gum. Ripe pods eaten or ground into flour which is mixed with tea or blood. | [18,36,39] |

| Albizia amara (Roxb.) B.Boivin | Mwowa, muundua, kiundua, muundua | Tree | [36,48] | Exudate, stems; produces an edible gum. Dried stems used as an additive in food or soup and as a meat tenderizer. | [36,39] |

| Bauhinia thonningii Schum. | Mukolokolo | Shrub or tree | [36,48] | Fruits, leaves; dry fruit pulp is edible. Young sour shoots used in porridge or chewed raw. | [18,36] |

| Crotalaria brevidens var. parviflora (Baker f.) Polhill | Kamusuusuu | Herb | [50] | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [36] |

| Eriosema shirense Baker f. | Ng’athu | Herb | [36] | Roots tubers; edible. | [36] |

| Craibia laurentii De Wild. | _ | Tree | Mwachala et al., 487 (EA) | Seeds; beans eaten after boiling for several hours. | [19] |

| #Vigna membranacea A.Rich. | Ithookwe | Climber | Gillett 19475 (EA) | Roots, leaves; leaves eaten as a vegetable. Roots eaten raw or roasted. | [19,20,36] |

| Vigna frutescens A.Rich. | _ | Climber | Bally B1536 (EA) | Root tubers; eaten raw or roasted. | [19,20,36] |

| Vigna praecox Verdc. | _ | Climber | SAJIT-Mutie MU0115 (HIB) | Roots; boiled or roasted and eaten. | [19] |

| #* Tamarindus indica L. | Kithumula, muthumula, kikwasu, nthumula, nzumula, ngwasu | Tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0208 (EA) | Fruits, leaves, seeds; fruit pulp eaten raw or used as a flavor in porridge or beer. Young leaves chewed raw or cooked as a vegetable. Seeds fried and eaten. | [18,22,36,39] |

| Tylosema fassoglensis (Schweinf.) Torre and Hillc. | Ivole | Climber | Hucks and Hucks 217 (EA) | Seeds, pods; seeds eaten raw, roasted or used as a coffee substitute. Unripe pods eaten raw. | [36] |

| #Vatovaea pseudolablab (Harms) J.B.Gillett | Kilukyo | Shrub or liana | [36] | Roots, leaves, flowers, pods, seeds; tubers cooked or roasted for food or eaten raw to quench thirst. Seeds eaten raw or cooked. Roots ground into flour and used for making porridge. Immature leaves, flowers and pods cooked as vegetables. | [19,20,36,39] |

| #Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp. | Nzuu | Shrub | [36] | Seeds; cooked and eaten. | [22,36,51] |

| Lablab purpureus (L.) Sweet | Mbumbu, ngiima, nzavi | Climber | [36] | Seeds, leaves; beans cooked and eaten. Leaves eaten as a vegetable. | [19,36] |

| * Vigna vexillata (L.) A.Rich. | _ | Climber | SAJIT-Mutie MU0257 (EA, HIB) | Roots; chewed raw to quench thirst. | [20] |

| #Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp. | Nzooko, nthooko | Climber | [36] | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [22,28] |

| Ormocarpum kirkii S.Moore | Muthingii | Shrub or tree | [48] | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [18,22,39] |

| Albizia anthelmintica Brongn. | Mwowa, kyalundathi, kyowa kisamba | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0194 (EA) | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [22,39] |

| Loganiaceae | |||||

| #* Strychnos decussata (Pappe) Gilg | Mutolongwe | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0109 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39,47] |

| * Strychnos henningsii Gilg | Muteta | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0200 (EA) | Roots, stems, bark, fruits; roots, stems and bark added to soup as a flavor. Fruits used for flavoring beer. | [18,36,39] |

| * Strychnos spinosa Lam. | Kyae, kimee, mae | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0162 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [36,39] |

| Malvaceae | |||||

| #* Azanza garckeana (F.Hoffm.) Exell and Hillc. | Kitotoo, Mutoo | Tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0289 (EA, HIB) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18,36,39] |

| #* Grewia tephrodermis K.Schum. | Mulawa, kikalwa, ngalwa, ilawa | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0220 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18,19,36,39,47] |

| #* Grewia villosa Willd. | Muvu | Shrub | SAJIT-Mutie MU0206 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18,19,36,39,47] |

| #Grewia mollis Juss. | _ | Shrub or tree | Thomas 671 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39,47] |

| * Grewia arborea (Forssk.) Lam. | Nguni | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0321 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39] |

| * Grewia forbesii Harv. ex Mast. | Mutalenda | Shrub, liana, tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0270 (HIB) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [36,39] |

| Grewia lilacina K.Schum. | _ | Shrub | Kirika et al., NMK462 (EA) | Fruits; edible. | [19] |

| Grewia similis K.Schum. | Mutuva | Shrub or liana | Edwards 681 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [19,36,39] |

| * Grewia tembensis Fresen. | Mutuva, nduva | Shrub | SAJIT-Mutie MU0242 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [19,36,39] |

| #Grewia tenax (Forssk.) Fiori | _ | Shrub | Kirika et al., NMK457 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [19,36,39,47] |

| Grewia trichocarpa Hochst. ex A.Rich. | _ | Shrub or tree | Lind and Agnew 5656 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [19,39] |

| Hibiscus greenwayi Baker f. | _ | Shrub | [52] | Leaves, stems; young leaves eaten raw. Sweet stems chewed raw. | [19] |

| #Adansonia digitata L. | Kiamba, muamba | Tree | Bally 11691 (EA) | Roots, leaves, seeds; Root tips eaten during famine. Roots of germinating seeds are edible. Young leaves eaten as a vegetable. Roasted seeds are edible. Seed pulp eaten raw or boiled and the juice used as a sauce or added to porridge. | [18,20,36,39,47] |

| #Corchorus olitorius L. | _ | Herb | [15] | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [15,22] |

| * Corchorus trilocularis L. | _ | Herb | SAJIT-Mutie MU0134 (EA) | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [36] |

| * Corchorus tridens L. | _ | Herb | SAJIT-Mutie MU0133 (HIB) | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [22] |

| Sterculia stenocarpa H.J.P.Winkl. | _ | Shrub or tree | Joana 7411 (EA) | Fruits; edible. | [19] |

| Moraceae | |||||

| * Dorstenia hildebrandtii var. schlechteri (Engl.) Hijman | _ | Herb | SAJIT-Mutie MU0281 (EA, HIB) | Roots; eaten raw. | [19] |

| Ficus capreifolia Delile | _ | Shrub or tree | Adamson 19716 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39] |

| * Ficus glumosa Delile | Kionywe | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0259 (EA, HIB) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [19,39] |

| Ficus populifolia Vahl | _ | Shrub or tree | Gillett 18574 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39] |

| #* Ficus sycomorus L. | Mukuyu | Tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0202 (EA) | Ripe fruits; figs eaten or dried and made into flour which is mixed with maize flour for making porridge. | [18,19,36,47] |

| Ficus sur Forssk | _ | Tree | [48] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [19,39,48] |

| Ficus vasta Forssk. | Mumbu, mukuyu | Tree | [48] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39,48] |

| Menispermaceae | |||||

| Chasmanthera dependens Hochst. | Uswe | Liana | SAJIT-Mutie MU0039 (EA) | Roots, stems; roots boiled in milk as a drink for a child. Stems are edible. | [19,20,39] |

| Nymphaeaceae | |||||

| * Nymphaea nouchali var. caerulea (Savigny) Verdc. | _ | Herb | SAJIT-Mutie MU0186 (EA) | Roots, flowers, fruits, seeds; edible. | [20,36] |

| Olacaceae | |||||

| #Ximenia americana L. | Kitula, mutula | Shrub or tree | [36] | Fruits, bark; ripe fruits are edible. Root bark used for tea. | [18,19,36,39,47] |

| Jasminum abyssinicum Hochst. ex DC. | Mukaksu | Climber | SAJIT-Mutie MU0154 (HIB) | Roots; roots boiled in broth or soup. | [20,39] |

| Olea europaea L. | Muthata, molialundi | Shrub or tree | [18] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18,39] |

| Olea capensis L. | ‘Elgon Olive, East African Olive’ | Tree | [18] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39] |

| Opiliaceae | |||||

| #Opilia campestris Engl. | Kiburuburu, mubrubru | Shrub | [18] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18,19,39,47] |

| Pedaliaceae | |||||

| * Sesamum calycinum Welw. | Luta | Herb | SAJIT-Mutie MU0081 (EA) | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [36] |

| Phyllanthaceae | |||||

| Antidesma venosum E.Mey. ex Tul. | Mukala, kitelanthia, kitolanthia | Shrub or tree | [36] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [36,39] |

| Bridelia scleroneura Müll.Arg. | _ | Shrub or tree | Bally 1567 [42] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39] |

| #* Bridelia taitensis Vatke and Pax ex Pax | Yathia, muandi, mwaanzia | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0039 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18,36,39,47] |

| #Flueggea virosa (Roxb. ex Willd.) Royle | Mukuluu, mukururu | Shrub | [48] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18,19,36,39] |

| Poaceae | |||||

| Dactyloctenium aegyptium (L.) Willd. | Ukuku | Herb | [36] | Roots, seeds; rhizomes chewed raw. Grains ground into flour or chewed raw. | [36] |

| Dactyloctenium giganteum B.S.Fisher and Schweick. | Ukuku | Herb | [36] | Seeds; grains ground into flour for making porridge. | [36] |

| Polygonaceae | |||||

| Oxygonum sinuatum (Hochst. and Steud ex Meisn.) Dammer | Song’e | Herb | Bally 13179 (EA) | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable or chewed raw. | [19,36] |

| Portulacaceae | |||||

| Portulaca oleracea L. | Kamama, kamumama, kinyukwi | Herb | [36] | Leaves, seeds; leaves and slender stems eaten raw or cooked as a vegetable. Seeds ground into flour for making porridge. | [36] |

| * Portulaca quadrifida L. | Kenyinyia, kamumama | Herb | SAJIT-Mutie MU0121 (EA) | Leaves, seeds; leaves and slender stems eaten raw or cooked as a vegetable. Seeds ground into flour for making porridge. | [36] |

| Putranjivaceae | |||||

| Drypetes gerrardii Hutch. | _ | Tree | Burry 4 (EA) | Fruits; eaten raw. | [19] |

| Rhamnaceae | |||||

| * Berchemia discolor (Klotzsch) Hemsl. | Kisanawa, kisaaya, nzaaya, nzanawa | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0293 (EA) | Fruits, exudate; ripe fruits are edible. Produces an edible gum. | [18,19,36,39] |

| #Ziziphus mucronata Willd. | Kitola usuu, kitolousuu, muae | Shrub or tree | [36,48] | Bark, fruits; ripe fruits are edible. Bark used in tea. | [18,19,36,39] |

| #Scutia myrtina (Burm.f.) Kurz | Mtanda mboo, kitumbuu, mbombo | Shrub or tree | [36] | Roots, fruits; ripe fruits are edible. Roots used in soup. | [18,19,36,39,47] |

| Ziziphus abyssinica Hochst. ex A.Rich. | Muae, kitolousuu | Shrub, liana or tree | [53] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [19,39] |

| Ziziphus pubescens Oliv. | _ | Shrub or tree | [42] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [36,39] |

| Ziziphus jujuba Mill. | _ | Shrub or tree | [36] | Ripe fruits; edible and made into flour. | [22,36,39] |

| Rubiaceae | |||||

| Canthium glaucum Hiern | _ | Shrub or tree | [36] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [36] |

| Pavetta gardeniifolia Hochst. ex A.Rich. | _ | Shrub | [54] | Fruits; edible. | [19] |

| #* Rothmannia urcelliformis (Hiern) Bullock ex Robyns | Mutendeluka | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0164 (HIB) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18] |

| #* Vangueria madagascariensis J.F.Gmel. | Kikomoa, mukomoa | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0280 (EA, HIB) | Ripe fruits; edible and used for flavoring beer. | [18,19,36] |

| Rothmannia fischeri (K.Schum.) Bullock ex Oberm. | Muendeluka | Shrub or tree | Owino and Mathenge 214 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39] |

| #* Tennantia sennii (Chiov.) Verdc. and Bridson | Kisilingu | Shrub | SAJIT-Mutie MU0207 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39,47] |

| #Vangueria infausta Burch. | Kikomoa, mukomoa, muteleli | Shrub or tree | Joana B1142 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [36,39,47] |

| Vangueria volkensii K.Schum. | Kikomoa, mukomoa | Shrub or tree | Gibbons OX635 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [36,39] |

| #* Vangueria schumanniana (Robyns) Lantz | Mukomole, kitootoo, ngomole, ndootoo | Shrub | Napper 1590 (EA) | Fruits, stems; ripe fruits are edible. Stems smoked and inserted into gourds of milk to induce good flavor in milk. | [36,39,47] |

| Vangueria apiculata K.Schum. | Kikomoa, mukomoa | Shrub or tree | [52] | Fruits; edible and used for flavoring beer. | [36,39] |

| * Meyna tetraphylla (Schweinf. ex Hiern) Robyns | Kitotoo, kitootoo, kakomoa, kitolousuu | Shrub or tree | Bally 1636 [42] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [36,39] |

| Rutaceae | |||||

| #* Zanthoxylum chalybeum Engl. | Mukenea, mukanu | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0317 (EA) | Bark, leaves, fruit; bark and fruits used as food spices. Leaves and fruits used in flavoring tea. Bark used in making or flavoring tea. | [18,36,39] |

| Vepris glomerata Engl. | _ | Shrub or tree | Trapnell 2406; Thomas 673 [42] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39] |

| * Vepris simplicifolia (Engl.) Mziray | Mutuyu | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0234 (EA, HIB) | Fruits; edible. | [19] |

| Harrisonia abyssinica Oliv. | Mkiliulu | Shrub or tree | Mutie MU0185 (HIB) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18,39] |

| * Zanthoxylum holtzianum (Engl.) P.G. Waterman | _ | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0180 (HIB) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [22] |

| Salicaceae | |||||

| Flacourtia indica (Burm.f.) Merr. | Kiathani, kikathani | Shrub or tree | Festo and Luke 2291 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [36,39] |

| Salvadoraceae | |||||

| #Dobera glabra (Forssk.) Juss. ex Poir. | Kisiu, kithio, kikaitha | Shrub or tree | Edwards EAH 12315 [42] | Exudate, fruits, seeds; produces an edible gum. Ripe fruits are edible. Boiled seeds are edible. | [18,36,39,47] |

| #Salvadora persica L. | Mukayau | Shrub or tree | Pearce 405 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18,19,36,39,47] |

| Santalaceae | |||||

| Osyris lanceolata Hochst. and Steud. | Kithawa | Shrub or tree | Birch 59/13 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39] |

| Sapindaceae | |||||

| Allophylus africanus P.Beauv. | _ | Shrub or tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0165 (HIB) | Fruits; edible. | [19] |

| #Pappea capensis Eckl. and Zeyh. | Kyuua, kiva, mba | Shrub or tree | [18,36] | Fruits, bark; ripe and unripe fruits are edible. Dry inner bark used for tea. | [18,36,39,47] |

| Haplocoelum foliolosum (Hiern) Bullock | Mukumu, mukumi | Shrub or tree | [54] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18,39] |

| Sapotaceae | |||||

| #Manilkara mochisia (Baker) Dubard | Kinako, kisaa | Tree | [36] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [18,36,47] |

| Solanaceae | |||||

| #Solanum americanum Mill. | Kitulu | Herb | [36] | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [21,22,36] |

| Talinaceae | |||||

| * Talinum portulacifolium (Forssk.) Asch. ex Schweinf. | _ | Herb | SAJIT-Mutie MU0014 (EA) | Leaves; eaten raw. | [19] |

| Verbenaceae | |||||

| Lantana camara L. | Kitavisi, mukiti, musomolo | Shrub | [36] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [36,39] |

| Lantana humuliformis Verdc. | _ | Shrub | Kuchar 14908 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [36] |

| Lantana ukambensis (Vatke) Verdc. | _ | Herb | Napier 1567 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [36] |

| Lippia javanica (Burm.f.) Spreng. | Muthiethi | Shrub | [18] | Fruits, leaves; ripe fruits are edible. Leaves used for tea. | [18,36] |

| Lippia kituiensis Vatke | Muthiethi, muthiiti, muthyeti | Shrub | [36] | Fruits, leaves; ripe fruits edible. Leaves used for tea. | [36,39] |

| Vitaceae | |||||

| Cissus aphyllantha Gilg | Mwelengwa | Shrub or liana | SAJIT-Mutie MU0247 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39] |

| Cissus rotundifolia Vahl | Itulu | Shrub | SAJIT-Mutie MU0128 (EA) | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39] |

| #Cyphostemma adenocaule (Steud. ex A.Rich.) Desc. ex Wild and R.B.Drumm. | _ | Climber | SAJIT-Mutie MU0143 (EA) | Leaves; eaten as a vegetable. | [22] |

| Xanthorrhoeaceae | |||||

| * Aloe secundiflora Engl. | Kiluma | Herb | SAJIT-Mutie MU0191 (EA) | Roots, flowers, peduncle; roots used to ferment traditional beer. Flower nectar is edible. Sweet base of inflorescence is chewed raw. | [36] |

| Zygophyllaceae | |||||

| #* Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Delile | Kilului, kiluluwi, mulului | Tree | SAJIT-Mutie MU0196 (EA) | Exudate, fruits, leaves, seeds; produces an edible gum. Ripe fruits are edible. Leaves and tender shoots eaten as a vegetable. Inner part of a seed is edible when boiled. | [18,36,39,47] |

| Balanites glabra Mildbr. and Schltr. | Kilului | Shrub or tree | [48] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [39] |

| Balanites pedicellaris Mildbr. and Schltr. | _ | Shrub or tree | [36] | Seeds, fruits; ripe fruits are edible. Inner part of the seed cooked and eaten. | [36,39] |

| Balanites rotundifolia (Tiegh.) Blatt. | Kilului | Shrub or tree | [36] | Fruit, seeds; fruit pulp is edible and used to make local brew. Inner part of seed is edible when cooked. | [36,39] |

| Balanites wilsoniama Dawe and Sprague | Kivuw’a | Tree | [32] | Ripe fruits; edible. | [36] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mutie, F.M.; Rono, P.C.; Kathambi, V.; Hu, G.-W.; Wang, Q.-F. Conservation of Wild Food Plants and Their Potential for Combatting Food Insecurity in Kenya as Exemplified by the Drylands of Kitui County. Plants 2020, 9, 1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9081017

Mutie FM, Rono PC, Kathambi V, Hu G-W, Wang Q-F. Conservation of Wild Food Plants and Their Potential for Combatting Food Insecurity in Kenya as Exemplified by the Drylands of Kitui County. Plants. 2020; 9(8):1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9081017

Chicago/Turabian StyleMutie, Fredrick Munyao, Peninah Cheptoo Rono, Vivian Kathambi, Guang-Wan Hu, and Qing-Feng Wang. 2020. "Conservation of Wild Food Plants and Their Potential for Combatting Food Insecurity in Kenya as Exemplified by the Drylands of Kitui County" Plants 9, no. 8: 1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9081017