January 2023 152

NEWS BSBI

BSBI ADMINISTRATION

President MICHELINE SHEEHY SKEFFINGTON ‘Seagal’, Ballynacourty, Clarinbridge, Co. Galway, Ireland

Hon. General Secretary and BSBI Company Secretary

Chair of the Trustees

Membership Secretary (Payment of subscriptions and changes of address) and BSBI

News distribution

Hon. Field Meetings Secretary (including enquiries about field meetings)

Panel of Referees & Specialists (comments and/or changes of address)

BSBI News – Editor

British & Irish Botany – Editorin-Chief

BSBI Chief Executive

BSBI Finance Manager (all financial matters except Membership)

BSBI Communications Officer (including publicity, outreach and website; British & Irish Botany)

BSBI Fundraising Manager (including donations, legacies, grants and organisational support)

BSBI Head of Science

BSBI Scientific and England Officer (& V.c. Recorders – comments and/ or changes of address)

BSBI Scotland Officer

STEVE GATER

28 Chipchase Grove, Durham DH1 3FA

CHRIS MILES

Braeside, Boreland, Lockerbie DG11 2LL

GWYNN ELLIS

41 Marlborough Road, Roath, Cardiff, CF23 5BU Please quote membership number on all correspondence; see address label on post.

JONATHAN SHANKLIN

11 City Road, Cambridge CB1 1DP

MARTIN RAND (with assistance from Jo Parmenter)

3 Kings Close, Chandler’s Ford, Eastleigh SO53 2FF

JOHN NORTON

215 Forton Road, Gosport PO12 3HB

IAN DENHOLM

3 Osier Close, Melton, Woodbridge IP12 1SH

JULIA HANMER

65 Sotheby Road, London N5 2UP

JULIE ETHERINGTON

Church Folde, 2 New Street, Mawdesley, Ormskirk L40 2QP

LOUISE MARSH

SARAH WOODS

23 Bank Parade, Otley LS21 3DY

KEVIN WALKER

Suite 14, Bridge House, 1–2 Station Bridge, Harrogate HG1 1SS

PETE STROH

c/o Cambridge University Botanic Garden, 1 Brookside, Cambridge CB2 1JE

MATT HARDING

c/o Royal Botanic Garden, Inverleith Row, Edinburgh EH3 5LR

BSBI Ireland Officer PAUL GREEN

Yoletown, Ballycullane, New Ross, Co. Wexford, Y34 XW62, Ireland

BSBI Countries Support Manager JAMES HARDING-MORRIS

BSBI Training Coordinator (FISC and Identiplant)

20 Manchester Square, New Holland, Barrowupon-Humber DN19 7RQ

CHANTAL HELM

BSBI Database Officer TOM HUMPHREY

BSBI Book Sales Agent

PAUL O’HARA

Summerfield Books, The Old Coach House, Skirsgill Business Park, Penrith, CA11 0DJ

BSBI website: bsbi.org BSBI News: bsbi.org/bsbi-news

micheline.sheehy@nuigalway.ie

Tel. 00 353 91 790311

steve.gater@bsbi.org

Tel. 07823 384083

chris.miles01@btinternet.com

Tel. 01576 610303

gwynn.ellis@bsbi.org

Tel. 02920 332338

fieldmeetings@bsbi.org

Tel. 01223 571250

VC11recorder@hantsplants.net

Tel. 07531 461442

john.norton@bsbi.org

Tel. 02392 520828

bib@bsbi.org

Tel. 07725 862957

julia.hanmer@bsbi.org

Tel. 07757 244651

julie.etherington@bsbi.org

Tel. 07944 990399

louise.marsh@bsbi.org

Tel. 07725 862957

sarah.woods@bsbi.org

Tel. 07570 254619

kevin.walker@bsbi.org

Tel. 01423 858327 or 07807 526856

peter.stroh@bsbi.org

Tel. 01832 720327 or 01223 762054

matt.harding@bsbi.org

Tel. 07814 727231

paul.green@bsbi.org

Tel. 00 353 87 7782496

james.harding-morris@bsbi.org

Tel. 07526 624228

chantal.helm@bsbi.org

Tel. 07896 310075

tom.humphrey@bsbi.org

info@summerfieldbooks.com

Tel. 01768 210793

CONTENTS January 2023 No. 152

Including welcome to new staff, reports from the 2022 AGM and BSBI conference, meetings update,

Cover photo: Toothwort (Lathraea squamaria), Sheepleas, Surrey, March 2022. Chris Heath. One of the images submitted in the Spring category for the 2022 BSBI Photographic Competition. See pp. 60 & 80

Contributions for future issues should be sent to the Editor, John Norton (john.norton@bsbi.org)

The Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland (BSBI) is the leading charity promoting the enjoyment, study and conservation of wild plants in Britain and Ireland. BSBI is a company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales (8553976) and a charity registered in England and Wales (1152954) and in Scotland (SC038675). Registered office: 28 Chipchase Grove, Durham, DH1 3FA. All text and illustrations in BSBI News are copyright and no reproduction in any form may be made without written permission from the Editor. The views expressed by contributors to BSBI News are not necessarily those of the Editor, the Trustees of the BSBI or its committees. BSBI ©2022 ISSN 0309-930X

FROM THE PRESIDENT / EDITORIAL 1 ARTICLES Changes to the heath vegetation of the Wirral Peninsula Eric Greenwood 3 The flora of a suburban garden and change over time Tony F. Marshall 11 Callitriche palustris (Narrow-fruited Waterstarwort): a Cumbrian annus mirabilis Jeremy Roberts 18 Two early records of the rare Rumex rupestris (Shore Dock) David Pearman 23 Modelling the history of Pyrola minor (Common Wintergreen) over 200 years in Berwickshire (v.c. 81) Michael Braithwaite 25 Ivy confusions? Alison Rutherford 28 Caltha palustris var. radicans: overlooked and under-recorded? Richard Lansdown & Tim Pankhurst 31 Take the risk – do a FISC! Sarah Whild & Sue Dancey 34 BEGINNER’S CORNER Making sense of mouse-ears Mike Crewe 37 ADVENTIVES & ALIENS Adventives & Aliens News 28 Compiled by Matthew Berry 41 Does Doronicum × longeflorens occur in Britain and Ireland? Erik Christensen 49 Artemisia austroyunnanensis Y. Ling & Y.R. Ling (‘Giant Mugwort’) in v.c.16 (West Kent) Rodney Burton 51 Printed in the UK by Henry Ling Ltd, Dorchester on FSC™ certified paper using ink created

renewable materials.

with

Cicerbita macrophylla subsp. macrophylla (Blue Sow-thistle) in v.c. 64 (M.W. Yorkshire) Howard Beck 53 Dispersal of Oxalis corniculata (Procumbent Yellow-sorrel) Rodney Burton 54 NOTICES

Panel of VCRs, Plant Atlas launch schedule, BSBI Photographic Competition and contents of British & Irish Botany 4:3 56 COUNTRY ROUNDUPS Botanical news from around England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland Compiled by Pete Stroh 62 OBITUARIES Compiled by Chris Preston 74 REVIEWS Compiled by Clive Stace 76 Importing PDF into Indesign Select “Show Import Options” when importing and choose “Crop to: Trim” and tick box for “Transparent Background”. This just includes the white, no arrows etc. The white box denotes the clear space the logo must have around it. Be careful when placing the logo that the white box doesn’t obscure anything. The logo below is at the minimum size allowed so cannot be reduced further but could be enlarged if appropriate, but the white background must be enlarged by the same amount too.

FROM THE PRESIDENT

Well,as I said at the Annual Conference in November, it’s like buses. We wait for decades for a female president (Mary Briggs, the first in 1998) – and then two come along at once! I hope to learn from them both in my presidency. But, even more incredible, I am only the second president from the Republic of Ireland … after D. A. Webb, who is also a hard act to follow. One thing I aim to do from the start is to put Ireland more on the map and in May 2023, we will host the Annual Summer Meeting in Killarney. We have a vibrant young group involved and it’s shaping up well with Atlantic oak woodlands, bogs, lakes, possibly islands, to explore – and maybe mountain exploring for the more intrepid.

One thing Ian Denholm was already keen to do as president, is to bring together different societies together, preferably in the field. We both hit on collaborating with the Royal Entomological Society to organise a one-day outing to Daneway Banks Reserve where the Large Blue butterfly resides. It’s now happening in June. I am keen to emphasise management of sites for conservation, but often, management for plants can be detrimental to invertebrates; the structure of a sward is at least as important. And of course, butterflies, like many invertebrates, feed on different plants in their larval stage. Daneway Banks is small and because we will be in the Large Blue season, it is limited to 30 people –sadly that means just 15 per society. However, I

EDITORIAL

AsI write this on New Year’s Eve it’s pouring with rain for the second day running, but I’m still looking forward to getting out over the next couple of days to take part in the BSBI’s New Year Plant Hunt. As usual I will concentrate on the built up habitats (walls, pavements, kerbs and urban grass verges), which usually prove to be the most fruitful places for finding plants in flower at this time of year – and hopefully it should be relatively dry underfoot. I hope the awful winter weather will soon abate so that we can all look forward to seeing the winter annuals

have a plan to initiate a similar event in Ireland with our National Parks & Wildlife Service that might be a two-day event in 2024. So watch this space!

We were all delighted to meet up at last at the Natural History Museum in November and 2023 promises well with lots of field excursions and events. My aim is to attend as much as I can. But I have resolved not to fly where at all possible. So I am very grateful for the offer to keep me on zoom for now for the meetings. That frees me up to visit each country for at least one field meeting over the next two years –including the Channel Islands and hopefully a return visit to the Isle of Man.

Of course March 2023 is filled with the Atlas launch. There has been huge build-up to this truly magnum opus. It has much more information this time, including analysis of trends which should inform conservation practitioners. For what are we doing all this recording for, if not to be of benefit to the conservation of our flora and habitats? This should become central to all our activities in future years. But it’s essential still to keep monitoring in the field and contribute locally where threats are perceived. In the meantime, here’s to a great launch and fabulous read for many years to come!

Micheline Sheehy Skeffington michelinesheehy@gmail.com

(which more typically flower during February and March in mild winters) as well as the early spring flowers which help brighten up botanising in the early part of the year. In this regard Mike Crewe’s Beginners Corner article on Mouse-ears (Cerastium spp.) (p. 37 ), might come in useful. I hope you enjoy this and the other articles in this issue and I wish members happy plant-hunting in 2023.

John Norton john.norton@bsbi.org

2 BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023 FROM THE PRESIDENT / EDITORIAL

Changes to the heath vegetation of the Wirral Peninsula

ERIC GREENWOOD

ERIC GREENWOOD

The Wirral peninsula (v.c. 58, Cheshire) extends for 27 km (17 miles) north-west of Chester. It is 8–13 km (5–8 miles) wide and is bounded on the north-east side by the Mersey estuary, on the south-west side by the Dee estuary and on the northwest side by the Irish Sea. Running parallel to the Mersey and Dee estuaries are two low sandstone ridges. Nearest to the Mersey are Bidston, Oxton and Storeton heaths, whilst on the Dee side there are Grange Hill (West Kirby), Caldy, Irby and Thurstaston Commons and Heswall Common. Large portions of these heaths were extant in 2022 but Heswall is fragmented into the Beacons, the Dales and Cleaver Heath with smaller fragments at Poll Hill, Whitfield Common and elsewhere. As their names suggest heaths refer to flat land on acid soils supporting ericaceous dwarf shrubs such as Calluna vulgaris (Heather). Within this dominant vegetation there may be variation with wetter and drier parts and even localised mire and flushed areas. In areas with deeper soils farms were established within the heath, e.g. Benty Farm at Thurstaston or Dale Farm

Above: Bidston Heath in 2022 from near where Ellis took his photo (see p. 5). The trees have completely hidden the mill. Barbara Greenwood

at Heswall. Burdett’s map of Wirral (1777, Figure 1) shows the heaths criss-crossed by tracks.

In addition to those on the sandstone outcrops other heaths in the south-east of the peninsula include Thornton Common and Flatt Heath, Willaston, but Burdett’s map indicates further fragments around Brimstage, Neston and Eastham. These heaths were situated on boulder clay overlying sandstone but so far as is known there were no rock exposures. Leaching of the basic clay must have occurred over many years to give rise to heaths, or alternatively the heaths developed on less calcareous glacial sands and gravels. Anderson (2021) described a similar situation with the development of heaths on the limestone plateau of the Peak District.

Whatever the substrate, heaths have an anthropogenic origin as grazed common lands. Without grazing they would be deciduous woodland

BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023 3

Changes to the heath vegetation of the Wirral Peninsula

(see below). I am unaware of any detailed historical surveys of Wirral heaths but it is likely that the sequence of events follows a similar pattern to those in southern England. Following the retreat of the ice after the last ice age, woodland covered much of lowland England. From about 5000 BP Neolithic farmers started to make clearings in the forest and as time passed these clearances became larger. The thin acid soils on the sandstone of Wirral probably supported a fairly open birch-oak woodland possibly

with some pine. The land would have been grazed from earliest times with the woodland changing to heath. Continued grazing maintained the heath vegetation (Webb, 1986). After most woodland had been reclaimed for farms, by Anglo-Saxon times the acid heaths remained as open common land. The local population had rights to the common, most importantly pasturage, the rights to graze domestic animals and possibly estover, the right to gather wood or herbage (bracken and gorse).

4 BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023

Figure 1. Burdett’s map of Wirral, part of his map of Cheshire 1777. Reproduced courtesy of Cheshire History Association.

During the 18th century there was considerable pressure to enclose the commons for various purposes, ranging from improving the lands for farming or even for building towns and villages. Nearby Liverpool may have developed in this way (Hosking & Stamp, 1963). Details of the enclosure of the Wirral heaths is not certain but there are enclosure awards for Thornton (1815), Heswall (1859) and Thurstaston (1883) at the Chester Record Office. According to Hosking & Stamp (1963) rights of grazing and pasture still existed for part of Thurstaston Common in the 1960s.

At some stage grazing ceased on all the Wirral heaths and commons but there is no record of when this happened. In recent years limited conservation grazing has been introduced to parts of Thurstaston Common. On other areas, e.g. Oxton Common, which is now a golf course, some cutting of the heath (in the roughs) is practised. Heswall Dales and Cleaver Heath are managed as nature reserves with management limited to preventing scrub encroachment.

The vegetation

Early Liverpool floras (Hall, 1839; Dickinson, 1851) list the heath species found from the early 19th century but gave no indication of the vegetation types present. Green (1933) and Newton (1971) provide lists of some of the characteristic or notable species. Green divides his lists into dry and wet heaths and into Bidston/Oxton and Heswall/ Thurstaston groups. By then many changes had already taken place so that they were unable to describe the flora and vegetation that the earliest botanists had encountered (Hall, 1839; Dickinson, 1851). However, it is possible to define four plant communities that were still present in the 1970s and 80s when Rodwell (1991a, b) and his collaborators did their field work. These communities were H9

Calluna vulgaris-Deschampsia flexuosa heath; H8 Calluna vulgaris-Ulex gallii heath; M16 Erica tetralix-Sphagnum compactum wet heath and W16 Quercus spp.-Betula spp.-Deschampsia flexuosa woodland.

H9 and H8 are typical dry heaths whilst M16 is usually wet throughout the year. It is likely these

and variations of these, existed in the early 19th century along with flushed communities, which have now disappeared. Over the years floristic diversity has decreased with the loss of rarer and perhaps characteristic species. In particular, the species known to have occurred on or near the heaths must have existed in flush communities with some base enrichment. What was known as the ‘Pinguicula field’ at the Raby Mere end of Thornton Common, well-known to local botanists (Green, 1902), was probably a stream-side flush. Pinguicula vulgaris and Carex pulicaris were typical of flushed communities and to a lesser extent so was Carex echinata

In addition to the open heath communities, woodlands also covered part of the sandstone ridges. These are now more extensive than in the 19th century. Rodwell (1991a) identified these as W16 Quercus spp.-Betula spp.-Deschampsia flexuosa woodlands. They are characteristic of the warm and dry south-eastern lowland zone of British vegetation. On Wirral, birch species are commoner than oak but identifying the species is more difficult. Both Betula pendula (Silver Birch) and B. pubescens (Downy Birch) are perhaps equally frequent, with numerous intermediates or hybrids. Both Quercus robur (Pedunculate Oak) and Q. petraea (Sessile Oak) are present but most oaks are the hybrid Q. × rosacea Rodwell (1991a) recognises two sub-communities: Quercus robur (W16a) and Vaccinium myrtillus-Dryopteris dilatata (W16b). He recorded the presence of the Quercus robur sub-community on Wirral but on some

BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023 5

Bidston Mill and heath c. 1900. Photo taken from Green (1933), which was first published in his Flora of 1902. The photograph was taken by J.W. Ellis, probably in the 1890s.

Changes to the heath vegetation of the Wirral Peninsula

of the Wirral heaths large parts of the ground flora are dominated by Dryopteris dilatata (Broad Buckler-fern) suggesting that the Vaccinium myrtillusDryopteris dilatata sub-community characteristic of more oceanic conditions is also present. The range of vegetation types found on Wirral heaths are at the north-western edge of their range in Britain (Rodwell, 1991a, b) and at the northern edge of the lowland zone as defined by Rackham (2003).

Floristic changes

Without accurate data it is difficult to measure change. Nevertheless, the 19th century Liverpool floras recorded the observations of local botanists. Much of their work was brought together by De Tabley with his own observations up to about 1875. His Flora of Cheshire was updated by his son and published in 1899. In 1902 Green published a Flora of the Liverpool District based on the observations of the Liverpool Naturalists’ Field Club during the previous eight or nine years. This gave detailed localities and the names of recorders. In 1933 he published a new edition but this gave much less precision. New records were incorporated into this edition but it is not clear to what extent old records were verified as still being present.

In 1971 Newton published his Flora of Cheshire based on his own records and those of his collaborators. A supplement was published in 1990. De Tabley, Green and Newton all devoted paragraphs describing the Wirral heath flora. Since 1990 records were published online in the BSBI database.

Given these limitations, tables have been prepared showing the known losses up to 1933 (Table 1) and since 1933 (Table 2.) Table 3 lists heath species that are thought to still occur on the Wirral heaths, with a summary of all three tables presented in Table 4.For each species, selected attributes (Hill et al., 2004) are given together with their IUCN threat status in England (Stroh, et al., 2014). Overall, the heath flora is characteristic of nutrient poor soils and climatically is typical of northern temperate areas of Europe that do not extend eastwards far into Asia. The heaths comprise both wet and dry areas.

Comparison with recent studies

Comparing the attributes of the lost species with those currently found on the heaths, the overall characteristics seem little different. The geographical affinities are very similar. If climatic change was taking affect it might be in the area of oceanicity, but the flora does not appear to be getting any less or more oceanic. However, it does appear that species requiring a wetter substrate are being lost and remaining species need less wet conditions. This was one of the conclusions reached by Ash et al. (2021) in their 39-year study of fixed quadrats on Thurstaston Common. They also suggested that there was some evidence for nutrient enrichment, because species currently have a preference for more fertile conditions. This could be from atmospheric deposition but also through changes induced by invading birch (Ashburner & McAllister, 2013; Mitchell et al., 1997, 2007, 2018).

Perhaps the most surprising observation in this study is that conditions appeared to have got more acidic in the first half of the 20th century with the loss of species requiring some base enrichment but with no increase in acidity after the 1930s. Sandstone soils are acid lacking bases but it is possible that springs arose where boulder clay was in juxtaposition with the acid sandstone. Similar conditions must have been present on the eastern side of Thurstaston Common where similar species were recorded. Until recently, flushed areas were present on the Dales (part of what was once Heswall Common) but none now survive.

Anderson (2021) in her study of upland grasslands in the Peak District also observed an increasing tendency to acidification and suggested that this might be due to acid rain caused by atmospheric pollution with sulphur and nitrogen oxides from nearby industrial areas. However, recent evidence suggests that the acid rain peak has passed and there is evidence of soils becoming less acidic since the late 1990s (Mitchell et al., 2018). The evidence from the Wirral heaths appears to confirm this trend.

The tables also show the current threat level (based on recent population status) in England (Stroh et al., 2014). This shows that the most threatened

6 BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023

Changes

to the heath vegetation of the Wirral Peninsula

BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023 7

Species Threat level F R N E1 E2 Carex echinata (Star Sedge) NT 8 3 2 5 3 Carex pulicaris (Flea Sedge) NT 7 5 2 7 2 Eleocharis acicularis (Needle Spike-rush) NT 10 7 5 5 6 Eleogiton fluitans (Floating Club-rush) LC 11 4 2 8 1 Eriophorum vaginatum (Hare’s-tail Cottongrass) LC 8 2 1 2 6 Filago germanica (Common Cudweed) NT 4 6 4 8 3 Genista anglica (Petty Whin) VU 5 3 2 7 1 Hypericum elodes (Marsh St John’s-wort) NT 10 3 2 7 1 Linum radiola (Allseed) VU 7 4 2 7 3 Littorella uniflora (Shoreweed) LC 10 5 3 7 2 Lycopodiella inundata (Marsh Clubmoss) EN 9 2 1 5 3 Lysimachia minima (Chaffweed) EN 7 5 3 7 3 Omalotheca sylvatica (Heath Cudweed) EN 6 4 3 5 4 Oreopteris limbosperma (Lemon-scented Fern) LC 6 4 3 7 3 Persicaria minor (Small Water-pepper) LC 8 5 8 7 5 Pilularia globulifera (Pillwort) VU 10 4 2 7 2 Pinguicula vulgaris (Common Butterwort) VU 8 6 2 4 6 Potamogeton polygonifolius (Bog Pondweed) LC 10 4 2 7 2 Sagina subulata (Heath Pearlwort) NT 6 6 4 7 3 Sedum anglicum (English Stonecrop) LC 3 4 2 7 1 Selaginella selaginoides (Lesser Clubmoss) LC 7 6 2 4 6 Average 11.7 4.4 2.7 5.9 3.1 No. threatened = 13 (62%)

Table 1. Extinct species 1933 or before. Key to columns is shown after Table 4.

Species Threat level F R N E1 E2 Carex arenaria (Sand Sedge) LC 3 5 2 7 3 Carex demissa (Common Yellow-sedge) LC 8 4 2 5 6 Carex hostiana (Tawny Sedge) LC 9 6 2 7 3 Carex leporina (Oval Sedge) LC 7 5 4 5 4 Coeloglossum viride (Frog Orchid) VU 4 6 2 4 6 Drosera intermedia (Oblong-leaved Sundew) VU 9 2 1 7 2 Drosera rotundifolia (Round-leaved Sundew) NT 9 2 1 5 6 Eleocharis multicaulis (Many-stalked Spikerush) LC 9 4 1 7 2 Gentiana pneumonanthe (Marsh Gentian) NT 7 4 1 7 4 Huperzia selago (Fir Clubmoss) LC 6 2 2 2 6 Pedicularis sylvatica (Lousewort) VU 8 3 2 7 3 Polygala serpyllifolia (Heath Milkwort) NT 7 2 2 7 2 Scutellaria minor (Lesser Skullcap) LC 9 4 2 8 2 Trifolium ornithopodioides (Bird’s-foot Clover) LC 6 5 3 8 2 Average 7.2 3.8 1.9 6.1 3.6 No. threatened: 5 (45%)

Table 2. Extinct species post 1933.

Changes to the heath vegetation of the Wirral Peninsula

Changes to the heath vegetation of the Wirral Peninsula

8 BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023

Species Threat level F R N E1 E2 Agrostis capillaris (Common Bent)* LC 5 4 4 5 4 Anthoxanthum odoratum (Sweet Vernalgrass) LC 6 4 3 6 4 Avenella flexuosa (Wavy Hair-grass)* LC 5 2 3 5 3 Betula pubescens (Downy Birch) LC 7 4 4 5 4 Betula pendula (Silver Birch) LC 5 4 4 5 4 Betula × aurata (Hybrid Birch) – – – – – –Blechnum spicant (Hard Fern) LC 6 3 3 7 3 Calluna vulgaris (Heather)* NT 6 2 2 5 3 Campanula rotundifolia (Harebell) NT 4 5 2 5 6 Carex binervis (Green-ribbed Sedge) LC 6 3 2 7 1 Carex nigra (Common Sedge)* LC 8 4 2 5 4 Carex pilulifera (Pill Sedge)* LC 5 3 2 7 3 Ceratocapnos claviculata (Climbing Corydalis) LC 5 4 5 7 1 Cytisus scoparius (Broom)* LC 5 4 4 7 3 Danthonia decumbens (Heath Grass) LC 6 4 2 7 3 Digitalis purpurea (Foxglove) LC 6 4 5 8 2 Dryopteris affinis subsp. affinis (Golden-scaled Male-fern) LC 6 5 5 7 3 Dryopteris dilatata (Broad Buckler-fern)* LC 6 4 5 7 3 Dryopteris filix-mas (Male-fern) LC 6 5 5 7 6 Epilobium montanum (Broad-leaved Willowherb) LC 6 6 6 7 3 Erica cinerea (Bell Heather)* NT 5 2 2 7 1 Erica tetralix (Cross-leaved Heath)* NT 8 2 1 7 2 Eriophorum angustifolium (Common Cottongrass)* VU 9 4 1 3 6 Festuca ovina (Sheep’s-fescue)* LC 5 4 2 5 5 Galium saxatile (Heath Bedstraw)* LC 6 3 3 7 2 Hieracium vagum (a hawkweed) LC – – – – –Holcus mollis (Creeping Soft-grass)* LC 6 3 3 7 3 Hypericum pulchrum (Slender St John’s-wort) LC 5 4 3 7 2 Hypochaeris radicata (Cat’s-ear)* LC 4 5 3 8 3 Juncus bulbosus (Bulbous Rush)* LC 10 4 2 5 3 Juncus effusus (Soft-rush)* LC 7 4 4 8 3 Juncus squarrosus (Heath Rush)* LC 7 2 2 7 2 Lonicera periclymenum (Honeysuckle)* LC 6 5 5 8 2 Lotus corniculatus (Common Bird’s-foottrefoil) LC 4 6 2 8 5 Luzula campestris (Field Wood-rush) LC 4 5 2 7 3 Luzula multiflorum subsp. congesta (Heath Wood-rush)* LC 6 3 3 3 6 Lythrum portula (Water-purslane) LC 9 5 3 7 3 Molinia caerulea (Purple Moor-grass)* LC 8 3 2 5 4 Nardus stricta (Mat-grass)* NT 7 3 2 5 3 Narthecium ossifragum (Bog Asphodel)* LC 9 2 1 5 1 Pinus sylvestris (Scots Pine)* – 6 2 2 4 5 Populus tremula (Aspen) LC 5 5 6 5 5

Table 3. Extant species 2021. Key to columns is shown after Table 4.

* Thurstaston Common species listed by Newton (1971).

Table 4. Average values for PLANTATT attributes taken from tables 1–3.

Key to tables

England Red List threat levels: VU = Vulnerable; EN = Endangered; NT = Near threatened; LC = Least concern.

Attribute (Hill et al., 2004):

F = Moisture: 1 = extreme dryness, 7 = constantly wet, 12 = submerged.

R = Reaction: 1 = extremely acid, 9 = calcareous, high pH soils.

N = Fertility: 1 = extremely infertile, 9 = extremely rich or near polluted.

Geographical affinities: E1 = Major biogeographic element, major biome. 1 = arctic-montane, 9 = Mediterraneanatlantic; E2 = Biogeographic, eastern limit. 1 = oceanic, 5 = Eurasian, 6 = circumpolar.

species were already lost by 1933, whilst today very few threatened species remain on Wirral heaths. This suggests that the heaths have lost the majority of the most notable species that made them particularly significant. If, as seems likely, the main reason for the losses is the gradually increasing dryness of the heaths and the absence of grazing with the accompanying invasion by birch scrub, then longterm reasons need to be sought for this change, which seems to be continuing. At present there is no satisfactory explanation.

Discussion

This study suggests that most of the rarer species characteristic of Wirral heaths were lost before 1900 or not long afterwards. The primary cause of this loss appears to be the long-term drying out of the heaths together with management changes. At present it is not clear what is causing the drying out; possibly complex factors involving ground-water hydrology. The heaths were common land used for grazing animals and for the gathering of herbage. These management changes enabled the spread of oak-

BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023 9 Potentilla erecta (Tormentil)* NT 7 3 2 5 4 Pteridium aquilinum (Bracken)* LC 5 3 3 7 6 Quercus petraea (Sessile Oak)* LC 6 3 4 7 3 Quercus robur (Pedunculate Oak) LC 5 5 4 7 3 Quercus × rosacea (Hybrid Oak) – – – – – –Salix caprea (Goat Willow) LC 7 7 7 5 5 Salix cinerea subsp. oleifolia (Grey Willow) LC 8 6 5 5 4 Salix repens var. repens (Creeping Willow) NT 7 6 3 5 4 Senecio sylvaticus (Heath Groundsel) LC 5 5 6 7 3 Solidago virgaurea (Goldenrod) NT 5 4 3 5 5 Sorbus aucuparia (Rowan)* LC 6 3 4 4 1 Trichophorum germanicum (Common Deergrass)* LC 8 2 1 4 6 Ulex europaeus (Gorse) LC 5 5 3 7 1 Ulex gallii (Western Gorse)* LC 6 3 2 7 1 Vaccinium myrtillus (Bilberry) LC 6 2 2 4 4 Average 6.2 3.8 3.2 6.0 3.4

(18%)

No. threatened = 9

F R N E1 E2 % threatened Extinct before 1933 (21 spp.) 11.7 4.4 2.7 5.9 3.1 62 Extinct post 1933 (13 spp.) 7.2 3.8 1.9 6.1 3.6 36 Extant 2021 (53 spp.) 6.2 3.8 3.2 6.0 3.4 18

Table 3 (cont.)

Changes to the heath vegetation of the Wirral Peninsula

Changes to the heath vegetation of the Wirral Peninsula

birch woodland but primarily the increase in birch species. Photographic and anecdotal evidence suggests that the development of birch woodland is accelerating, invading not only the dry heath but also the remaining fragments of wet heath (see photographs). This change is probably too far advanced for any conservation measures to reverse the process (Mitchell et al., 1997, 2007). The resultant woodland may, in time, not be too dissimilar to the oak-birch woodland from which the heaths were originally derived, where patches of more open habitats were probably maintained by large herbivores and early anthropogenic clearances (Vera, 2000), which would have enabled species of more open heath habitats to survive or flourish.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Barbara Greenwood and Professor Rob Marrs for comments and checking the script and to Dr Hilary Ash and members of Wirral Wildlife for botanical data.

References

Anderson, P. 2021. Peak District. The New Naturalist Library. HarperCollins, London.

Ash, H.J., Brockbank, A., Greenwood, B., Sixsmith, M., Baker-Schomer, M. & Marrs, R.H. 2021. Long-term monitoring of a heathland conservation project: a tale of twelve quadrats. Field Studies Journal 1: 1–23. fsj.fieldstudies-council.org (accessed 11/8/2022).

Ashburner, K. & McAllister, H.A. 2013. The genus Betula. Kew Publishing, Kew.

De Tabley, W. 1899. The Flora of Cheshire. Longmans, Green and Co. London.

Dickinson, J. 1851. The Flora of Liverpool. John van Voorst, Deighton and Laughton, Liverpool.

Green, C.T. 1902. The Flora of Liverpool District. D. Marples & Co., Liverpool.

Green, C.T. 1933. The Flora of Liverpool District. T. Buncle & Co., Arbroath.

Hall, T.B. [1839]. A Flora of Liverpool. Whitaker & Co., London.

Hill, M.O., Preston, C.D. & Roy, D.B. 2004. PLANTATT. Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Abbots Ripton.

Mitchell, R.J., Marrs, R.H., LeDuc, M.G. & Auld, M.H.D. 1997. A study of succession on lowland heaths in Dorset, southern England: changes in vegetation and soil chemical properties. Journal of Applied Ecology 34: 1426–1444.

Mitchell, R.J., Campbell, C.D., Chapman, S.J., Osler, G.H.R., Vanbergen, A.J., Ross, L.C., Cameron, C.M. & Cole, L. 2007. The cascading effects of birch on heather moorland: a test for the top – down control of an ecosystem engineer. Journal of Ecology 95: 540–550.

Mitchell, R.J., Hewison, R.L., Fielding, D.A., Fisher, J.M., Gilbert, D.J., Hurskainen, S., Pakemann, R.J., Potts., J.M. & Riach, D. 2018. Decline in atmospheric sulphur deposition and changes in climate are the major drivers on long-term change in grassland plant communities in Scotland. Environmental Pollution 235: 956–964.

Newton, A. 1971. Flora of Cheshire. Cheshire Community Council Publications Trust Limited, Chester.

Rackham, O. 2003. Ancient Woodland. Castlepoint Press, Dalbeattie.

Rodwell, J.S. (ed) 1991a. British Plant Communities, vol. 1 Woodlands. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Rodwell, J.S. (ed) 1991b. British Plant Communities, vol. 2 Mires and Heaths. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Stroh, P.A., Leach, S.J., August, T.A., Walker, K.J., Pearman, D.A., Rumsey, F.J., Harrower, C.A., Fay, M.F., Martin, J.P., Pankhurst, T., Preston, C.D. & Taylor, I. 2014. A Vascular Plant Red List for England. Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland, Bristol.

Vera, F.W.M. 2000. Grazing Ecology and Forest History. CABI Publishing, Wallingford.

Webb, N. 1986. Heathlands. The New Naturalist. Collins. London.

Eric F. Greenwood

We are sad to report that Eric Greenwood died in October 2022. He was one of the longest serving members of the Society and an Honorary Member since 1976. His obituary will appear in a future issue.

John Norton, Editor

10 BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023

Wet heath invaded by birch at Thurstaston, 2022. Eric Greenwood

The flora of a suburban garden and change over time

TONY F. MARSHALL

The garden and its history Gardens can be very biodiverse. Over time I have recorded nearly 1,300 species other than plants in my garden, some of them uncommon in the surrounding area – fungi, invertebrates and a few vertebrates. However, gardens differ from other ‘natural’ habitats in several ways. They are generally more sheltered with a slightly warmer microclimate, they tend to be small (but this is countered by the fact that separate gardens are often clustered together in close contiguity), and they are idiosyncratically managed according to the whim and aims of the gardener, typically involving the introduction of alien species and garden cultivars. Each is usually composed of several microhabitats, often each one small in extent, which may prevent (along with the owner’s selective management) the effective establishment of sustainable ecosystems, but can certainly create high biodiversity per unit area. Most microhabitats can support substantial wildlife, with the exception of extensive paving or oft-mowed lawns (although these can support different plants and creatures in their own right). Lawns, if not assailed by chemical moss-killers or fertilisers, can be excellent for fungi, although this is only realised if mowing is abandoned over autumn.

In the case of my garden, in the Chilterns near Great Missenden (v.c. 24), it is typically sheltered, but the largest part is on the shady colder north side of the house, and I have not noticed that any plants survive there that would not do so in the wild. It is certainly small (300 sq. m. in total), which does limit its capacity for the diversity and extent of microhabitats. Much of it is shaded by a tall hedge and acts essentially as a woodland floor, maintaining a number of true woodland species, but its size means that it cannot possibly rival the diversity or ecology of true woodland. In contact with similarly managed gardens its influence and wildlife value

might be much wider, but unfortunately none of the contiguous gardens are at all favourable to wildlife. The current habitats are three meadow areas (each left uncut until after flowers have seeded, but each with its own character), a hawthorn hedge with much holly and ivy (uncut and higher than neighbouring hedges; it is much used by birds), two mature trees – a Betula pendula (Silver Birch) which was a naturally occurring first-year seedling in 1983 and an older Salix caprea (Goat Willow), scrub, paving (which provides interstitial niches for certain plants), rockery and ‘scree’, and an area occasionally dug over (not often enough!), and side-passages that are shadier and moister than other areas, one supporting a series of ferns. There are also small wood piles and a marshy hollow that was once a pond, created in 1983, until the plastic liner perished, although it is still ‘watered’ by a hose extending from a waterbutt. Surrounding fences make access difficult for larger mammals, but we have had Foxes, Hedgehogs, Squirrels and Muntjac (not to mention Brown Rats) on occasion.

The soil is thin humus over slightly acidic sandy clay with flint pebbles, far from ideal for ‘proper’ gardening. Vegetable crops grow very poorly.

It is not particularly managed for aesthetic purposes, although the largest meadow can be attractive in early spring to early summer with a succession of flowers from bulb plants through Primula veris (Cowslip), P. vulgaris (Primrose) and Hyacinthoides non-scripta (Bluebell) until Silene dioica (Red Campion) and Allium triquetrum (Threecornered Garlic) take over, soon after which it is mown. Another meadow is best in early summer with Hypochaeris radicata (Cat’s-ear), Crepis vesicaria (Beaked Hawk’s-beard), Leucanthemum vulgare (Oxeye Daisy), Rumex acetosa (Common Sorrel) and Rhinanthus minor (Yellow-rattle), plus 19 species of Poaceae, but I have waited in vain so far for a more diverse flora to arrive

BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023 11 The

flora of a suburban garden and change over time

The flora of a suburban garden and change over time

(Fritillary), Myosotis sylvatica (Wood Forget-menot) and Caltha palustris (Marsh-marigold).

naturally: a meadow requires much patience and a long life! (While seeding may artificially increase diversity in the short term I find that the variety soon dwindles and, in a small area, soon becomes dominated by a few species best suited to the soil and climate.) This second meadow is mossy and contains four waxcap fungi, but they have yet to expand their population to put on a really great

show. A waxcap grassland takes as long to develop as a flower meadow, nature moving on a slower course than our human lives.

My primary aim is to provide a rich wildlife habitat with, as far as possible, a wide variety of plants. I prefer to leave the garden to its own devices (both from design and lack of time, or call it laziness), as it is interesting to observe the succession. Some

12 BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023

Plate 1. Corner of one meadow beside scrub, April, with Primula veris (Cowslip) (including red variety), Cardamine pratensis (Cuckooflower), Hyacinthoides non-scripta (Bluebell) and Taraxacum (Dandelion). Photographs by the author.

Plate 2. Another meadow in April, by former pond (top right) with native Narcissus pseudonarcissus (Wild Daffodil) going over, Cowslip emerging, Fritillaria meleagris

Plate 3. Same meadow as Plate 2 and wood edge, in June just before cutting, including Dryopteris filismas (Male-fern), Corylus avellana (Hazel), Euphorbia amygdaloides Wood Spurge, Betula pendula (Silver Birch), Silene dioica (Red Campion), Leucanthemum vulgare (Oxeye Daisy), Ranunculus repens (Meadow Buttercup), Hypericum androsaemum (Tutsan), Hesperis matronalis (Dame’s-violet), Allium roseum (Rosy Garlic) and A. triquetrum (Three-cornered Garlic).

Plate 4. Same meadow as shown in Plate 1, June, with Oxeye Daisy, Rumex acetosa (Common Sorrel), Crepis vesicaria (Beaked Hawk’s-beard) and a multitude of grass species.

action, however, is necessary if it is not to become a uniform thicket of scrub and tall grass. I have never used artificial chemicals or fertilisers. Each meadow is mown once a year, the cuttings taken off. Other than that the main pursuit is cutting back over-exuberant shrubs and other plants, of which we seem to have a lot, filling a green bin once a fortnight. (This is a good time to look out for galls,

leaf-mines and micro-fungi, incidentally.) The willow is pollarded every three or four years – I leave it in between because twice it has been visited by egglaying Purple Emperors. Each winter I intend to dig over the ‘cultivated’ area, but recent drought and the hard stony clay have made that very difficult. Occasional seeding or planting is undertaken when opportunity provides, but usually of native plants or

BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023 13

The flora of a suburban garden and change over time

The flora of a suburban garden and change over time

aliens known to become naturalised, except for some exotic bulbs to provide early spring interest before our natives appear. I would like to renew the pond, but my age prevents such an undertaking. Spilled bird-seed is an occasional source of alien plants.

I took over the garden in 1982, when it was only one year old. Two years later I carried out the first botanical survey, which has been supplemented by casual observations and occasional fuller surveys until the latest complete survey in 2022. Altogether 316 different plant taxa have been recorded, with 198 (63%) currently present.

The flora

(1)Naturally occurring natives

These make up 43% of species currently in the garden. Of the 158 species ever recorded, just over half still occur (85). There have been two major causes of losses in the garden. One is the demise of our pond, with the loss of five plants such as Callitriche (Water-starwort) and Lemna species (duckweeds). The other is the spread of shrubby plants and the loss of open regularly-forked soil, reducing the habitat for arable annuals, of which 21 species have been lost, like Lysimachia arvensis (Scarlet Pimpernel), Papaver rhoeas (Common Poppy) and, most notably, Linaria repens and Chaenorhinum minus (Pale and Small Toadflax). Two species appear to have been lost by converting short grass areas to wildflower meadows: Medicago lupulina (Black Medick) and Galium saxatile (Heath Bedstraw); and two more to the general drying out of the environment due to gradual climate change: Gnaphalium uliginosum (Marsh Cudweed), lost after 2008, and Solanum dulcamara (Bittersweet), lost after 2018. The majority of losses (43), however, remain unexplained, including all three Sonchus spp. (Sow-thistles), Trifolium pratense (Red Clover), Stellaria graminea (Lesser Stitchwort) and Plantago major (Greater Plantain), some of which still grow in the road verge immediately outside my garden, although one might speculate that some losses, such as lesser stitchwort, are due to soil nutrification by air-borne pollution which has reduced numbers of acidophilic plants generally in the region over the same period.

Most of the naturally occurring natives, as might be expected, spread naturally within the garden. Just seven remain present without showing signs of expanding their range. Two of these are recent arrivals, Iris foetidissima (Stinking Iris) and a Taxus baccata (Yew) seedling. One has only limited habitat availability, Typha latifolia (Bulrush). Polygonum aviculare (Knotgrass), Lonicera periclymenum (Honeysuckle) and Ribes uva-crispa (Gooseberry), not planted but naturally occurring, have been stable over a long period. The remaining species is the unexplained arrival of Des Etang’s St John’s-wort Hypericum × desetangsii in 2016, which has remained in situ now for six years, despite the garden never having hosted any other non-shrubby Hypericum

The most persistent spreaders in this group, which require regular removal are Geum urbanum (Wood Avens), Rubus spp. (Bramble) (mostly Rubus vestitus), Urtica dioica (Common Nettle), Hedera helix subsp. helix (Ivy), Carex sylvatica (Wood Sedge) and Geranium robertianum (Herb-Robert). It seems likely that all these are responding to the general nutrification of the local environment from air pollution. Perhaps the most surprising is Wood Sedge, which is happy, like the Wood Avens, to move from its natural shaded environment to just about anywhere in the garden.

More welcome natives, which spread more moderately, are Cardamine pratense (Cuckooflower), Fumaria officinalis (Common Fumitory), Leucanthemum vulgare (Oxeye Daisy), Hyacinthoides non-scripta (Bluebell), Lotus corniculatus (Common Bird’s-foottrefoil) (the native variety, not the more vigorous agricultural import), Primula veris (Cowslip), P. vulgaris (Primrose), and their naturally arising hybrid Primula × polyantha (often more vigorous than its parents and long-lasting). All these occur commonly in the surrounding local area. Of special interest is Geum × intermedium, a hybrid that arose in situ between Wood Avens and Geum rivale (Water Avens) that I planted beside the pond and is not native to the local area. The latter gradually disappeared, apparently hybridised out, while the hybrid flourishes alongside its other parent. The most recent additions to the naturally occurring native list are three plants that only arrived in 2022: Bromopsis ramosa (Hairy Brome),

14 BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023

a seedling Fagus sylvatica (Beech) and Torilis japonica (Upright Hedge-parsley). Why they took so long, I do not know.

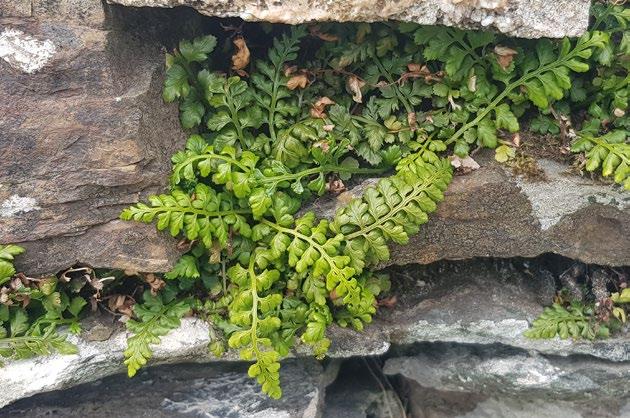

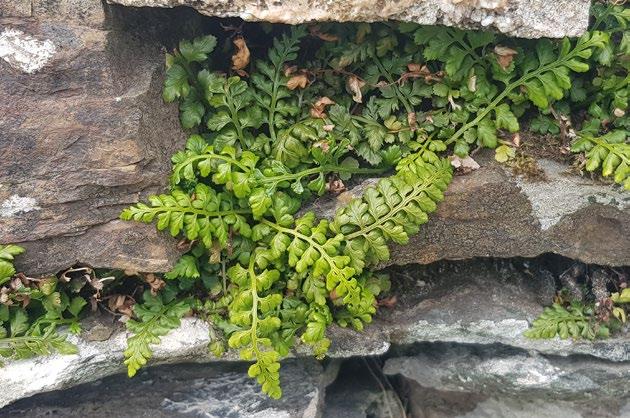

(2)Planted natives

These are native species that I have deliberately introduced at one time or another. They only constitute 14% of the total species present. Once introduced, their survival rate is quite high, twothirds still being present (68%). Of the 13 losses, seven are accounted for by the loss of the pond and therefore the disappearance of suitable habitat. Two of the others show a local preference for more calcareous soil and may have found our clay less to their liking – Briza media (Quaking-grass) and Silene vulgaris (Bladder Campion), neither are at all common in the immediate vicinity either. Another species was affected by its situation becoming overshaded and general drying out – Asplenium trichomanes (Maidenhair Spleenwort). It has similarly been lost from many of its native habitats locally. It is less clear why the three remaining planted natives failed to survive – Ajuga reptans (Bugle), Myrrhis odorata (Sweet Cicely) and Anemone nemorosa (Wood Anemone). All three survived several years and then suddenly failed to re-appear. Lack of moisture might be the reason for Bugle and Wood Anemone, while Sweet Cicely is one of those plants that just come and go anyway (it has disappeared from its only natural site locally, from which I took the seed).

On the other hand, quite a lot of the planted natives (64%) not only survived but are inclined to spread and may require control. The most vigorous seem to be Filipendula ulmaria (Meadowsweet) (which only grows locally by two other ponds where it was also introduced), Helleborus foetidus (Stinking Hellebore), Origanum vulgare (Wild Marjoram), Papaver cambricum (Welsh Poppy), Rhinanthus minor (Yellow-rattle) (but only within one meadow area), Silene dioica (Red Campion) (locally uncommon in natural habitats but can become a nuisance where introduced!), Galium verum (Lady’s Bedstraw), Carex otrubae (False Fox-sedge), Hypericum androsaemum (Tutsan) and Carex pendula (Pendulous Sedge) (a real thug, impossible to remove, a species that is

also increasing in local woodlands to the detriment of other flora and my biggest regret in causing its introduction to my garden). Apart from Carex pendula, none of these plants inclined to take over the garden are very common in more natural habitats. Two ‘native’ bulb plants also spread, but more gradually, Fritillaria meleagris (Fritillary) and Narcissus pseudonarcissus (Wild Daffodil). The original five fritillaries are now 12 flowering plants in 2022 (after 36 years!), plus about the same number that did not flower that year, while the 10 daffodils are now nearly 150 in 20 years. This contrasts with non-native daffodils that show no ability to spread at all, including Narcissus obvallaris (Tenby Daffodil) that remains established only in its original numbers.

(3)Naturally occurring aliens

Many species that invite themselves into our gardens, whether we want them or not, are aliens that have become established in natural habitats as well. These currently make up just 5% of my present garden species. They have a high loss rate of 64%, that is, they often come and go, but those that do remain can be a nuisance, as all of them are good at spreading themselves around. The lost aliens are almost all ‘casuals’ that seldom become naturalised and often derive from bird-seed, like Phalaris canariensis (Canary-grass), Camelina sativa (Gold-of-pleasure), Panicum miliaceum (Common Millet) and the Fleabanes Erigeron canadensis and E. floribundus. One was deliberately destroyed when it appeared in 1999 – Heracleum mantegazzianum (Giant Hogweed): there are limits to a laissez-faire approach to gardening!

Of those that have become established, few are so expansive as to become a nuisance, unlike some of our natives. The only one that is a bit of a problem is Centranthus ruber (Red Valerian), mostly in its white form. Sometimes, however, these uninvited aliens can be a pleasure to have. Potentilla recta (Sulphur Cinquefoil) arrived in 2019 and seems keen to stay. It is a handsome plant. The only problem is that its chosen habitat is at the base of our up-and-over garage doors, so that it regularly gets knocked over, but resolutely returns to its erect position and seems

BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023 15

The flora of a suburban garden and change over time

none the worse for wear. I hope it manages to seed itself into a more comfortable situation in time.

(4) Planted aliens

These plants, including garden cultivars of native species like Geranium sanguineum (Bloody Cranesbill), are normally the mainstay of a garden, but with our predilection for naturally occurring species, they only constitute 38% of our garden species. Some of them were planted before we arrived. Interestingly, they have a lower loss rate (15%) than any other group, because they are perennials and are generally designed to fare well in gardens. The ones that were lost do not seem to have any obvious reason, apart from Elodea canadensis (Canadian Pondweed) which disappeared with our pond. Lysimachia verticillaris (Whorled Loosestrife), for instance, had a period of expansion 1986–2009 and then suddenly dwindled and disappeared, perhaps as the ground became too dry.

Among the survivors, many such as shrubs remain where they are placed, but a good number (38%) are inclined to spread, some more notably than others. A few are very much inclined to take over, like Allium triquetrum (Three-cornered Garlic), whose introduction was a big mistake. It may spread by seed, but in any one year a single bulb may produce two dozen or more small bulblets, virtually impossible to remove from the soil completely when you try digging them up. One of our meadows, which has a beautiful spring display of bulb plants followed by Cowslips and Primroses, suddenly

becomes overwhelmed each summer by a mass of Three-cornered Garlic, its relative Allium roseum (Rosy Garlic) and introduced native Red Campion. Only a few Bluebell and a good number of Oxeye Daisy are left trying to hold the fort. Another thug is Pilosella aurantiaca (Fox-and-cubs), which spreads by seed and by stolons running both above and below ground.

Most shrubs are better behaved, but Prunus laurocerasus (Cherry-laurel) had been planted before we arrived. We have always tried to remove it but much still survives. At one stage its roots forced their way into our main drain and then blocked it completely. Whatever possessed the builders to plant a laurel boundary hedge beside the main drain line? There are many local woodlands where Cherry-laurel is becoming dominant and, it being of Mediterranean origin, the increasing desiccation of our woodlands will make the problem worse. Other willing spreaders include the garden form of Euphorbia amygdaloides (Wood Spurge), subsp. robbiae, Hieracium scotostictum (Spotted Hawkweed) (for which I have the late BSBI member Alan Showler to thank), Crocus tommasinianus (Early Crocus) – mostly in open grassland, but also seeding between paving stones, Hypericum calycinum (Rose-of-Sharon), Melissa officinalis (Balm) and Vinca major ‘Variegata’ (Greater Periwinkle).

Of our fifty planted aliens that survive but have not yet started spreading, 19 are bulb plants, especially cultivars of Narcissus pseudonarcissus and N. major, but also other species like N. bulbocodium The rest are a mixture of herbs like Geranium phaeum (Dusky Cranesbill) and Polygonatum × hybridum (Garden Solomon’s-seal) and typical garden shrubs like Berberis thunbergi, Fuchsia magellanica and Cotoneaster spp. Most do little to enhance the garden’s wildlife value except providing shelter and sometimes nesting sites, but I could recommend Skimmia japonica for its popularity with pollinating insects, as also is Origanum vulgare ‘Aureum’ (Marjoram). On the other hand the taxon most commonly sold as ‘Butterfly Plant’ Hylotelephium ‘Herbstfreude’, unlike the native Hylotelephium telephium (Orpine), produces no nectar at all and you do not see a butterfly anywhere near

16 BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023

The flora of a suburban garden and change over time

Potentilla recta (Sulphur Cinquefoil) – a chance arrival in 2019

it. Mention should also be made of our Laurus nobilis (Bay) which has grown considerably in the last two years and obviously feels our climate is now sufficiently Mediterranean to start to flourish and even supports its own leaf gall-forming species, Lauritrioza alacris (Bay Sucker), a Hemipteran bug. It flowers well – will it, too, start to seed and spread?

Changes to the flora over time

No flora, no ecosystem, is constant over time, but, compared to the likes of an established chalk grassland nature reserve, a garden is particularly prone to change, receiving regular human interference and particularly subject to infusion from nearby gardens. The natural succession seen in more ‘natural’ habitats is speeded up here, with constant chance incomers, short-lived casuals, occasional planting and seeding, and a little deliberate elimination. Only the mini-meadows and hedgerow show a little more stability and something approaching an ‘ecosystem’. These are the only places where soil-growing fungi are recorded, of which 102 species have been seen over the years, indicating a more stable system. (The mushrooms Agaricus osecanus and A. urinsacens provide us with many a meal if we get to them before the slugs.) Every year the garden is different and we enjoy the surprises, while sometimes mourning the losses. It is likely that the garden is at its maximum holding capacity after 40 years, given the number of microhabitats that can be sustained, but the composition always varies.

In the detailed account above, however, a few long-term changes can be detected. Loss of habitat (the pond, well-cultivated ground) has had a major effect on variety and number of species present, but that is down to management and could potentially be changed. On the other hand, there are two processes beyond the individual’s control: nutrification from air pollution and climate warming. The effect is seen both in the garden and the wider environment.

Nutrification often occurs from poorly controlled fertiliser spray on farmland and has caused substantial losses in the hedge-bottom flora of neighbouring fields: Anthriscus sylvestris (Cow Parsley), Common Nettle and Galium aparine (Cleavers) now

often dominate this habitat at the expense of all else. Our garden fortunately avoids this effect, but airborne nitrogen and phosphorus from transport and other sources are universal, so that plants greedy for nutrients thrive and out-compete others, reducing biodiversity. Plants requiring either calcareous or acid soils particularly suffer.

Last summer (2022) has made the gradual desiccation of our soils particularly noticeable, with young Quercus robur (Pedunculate Oak) dying and many smaller plants disappearing, especially wall ferns; Alchemilla xanthochlora (Pale Lady’s-mantle) has become extinct in the area in the last couple of years, and Gentianella germanica (Chiltern Gentian) flowered this year as small wizened plants. In the garden most plants have been affected to some degree with shortened flowering periods, reduced growth and trees dropping leaves. This desiccation appears to result from a change in typical weather patterns, with summer becoming more Mediterranean in type (but mostly without the plants suited to such a climate). The drop in numbers of hoverflies and other insects has been very marked over the last 40 years, and this could have an effect on plant pollination, although bees are still regular visitors, even if one of the commonest these days is the new coloniser from warmer climes, Bombus hypnorum (Tree Bumblebee), which regularly nests under our eaves.

The change in climate affects the composition of the fauna as well as the flora, so that we may already be seeing the start of a shift in the whole ecosystem towards species of a more continental climate, with exotic species gradually replacing long-established natives. Our gardens may represent the forefront of this process – and it is in them that we can most easily study and document the changes.

Acknowledgements

My wife Val gave considerable help with the surveys (and does the brunt of the garden management!).

Tony F. Marshall ecorocker@gmail.com

BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023 17

The flora of a suburban garden and change over time

Callitriche palustris (Narrow-fruited Water-starwort): a Cumbrian

annus mirabilis

JEREMY ROBERTS

Thisaccount of a small, elusive, intriguing, plant may I hope encourage searches in similar areas for what must be an under-recorded, and perhaps expanding, species.

Haweswater (v.c. 69, Westmorland) remains the only confirmed English location for Callitriche palustris (Narrow-fruited Water-starwort) (R.V. Lansdown, pers. comm.). It has been recorded more widely in Scotland in recent years, in v.c. 73 (Kirkcudbrightshire); several sites east of Loch Lomond in both v.cc. 86 and 99 (Stirlingshire and Dunbartonshire); and in single sites in v.cc. 87 and 89 (West and East Perthshire). In Ireland there are known sites in v.cc. H9 (Clare), H15 (S.E. Galway) and H17 (N.E. Galway). The plant is regarded as native (Stace, 2019). It has the widest global range of any Callitriche species (see Lansdown, 2008), over much of North America and Eurasia. Widespread across central and northern Europe it ‘peters out’ markedly to the west, being absent or local in the British Isles, western France and Iberia.

When Callitriche palustris was uncovered at Haweswater Reservoir in Cumbria in 2016 (Brown & Roberts, 2017) plants were scattered across an area of silt in the ‘drawdown zone’ at the head of the reservoir at an altitude of 230–240 m a.s.l. The water level on that day (in mid-July) was six vertical metres below its ‘typical high’ of 31.4 m (United Utilities, 2022). Searches in some later years found no further sign of the plant, and only small quantities of C. brutia or C. stagnalis (Intermediate and Common Water-starworts). In some years the drawdown was limited to the upper more gravelly and sandy reaches – perhaps unsuitable for germination of the plant – and in other years exposed mud was covered extensively in mats of rotting vegetation from various sources.

18 BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023

Typical patch of fruiting Callitriche palustris (Narrowfruited Water-starwort) with Gnaphalium uliginosum (Marsh Cudweed), Lythrum portula (Water-purslane) and Riccia sp. Jeremy Roberts

By September 2022, after the notably prolonged and dry summer, the drawdown zone was very extensive (water level 12 m below ‘typical high’ and a further 6 m below its July 2016 level). The old lane- and field-walls were exposed, and very large areas of mud and silt. John Poland was in contact to say that in a short trip ‘up north’ he was hoping to have a search for Callitriche palustris, with which he was unfamiliar. Based on previous experience I cautioned John about the uncertainties of success, entirely needlessly. Phill Brown and myself met John at the head of the reservoir on 6 September. In the areas where the plant had been in 2016 there was a scatter of water-starworts, and after some casting about John called ‘here’s some black fruits!’, and the hunt was on!

The receding waterline was hundreds of metres further, and proceeding down the gently-shelving expanses of (thankfully firm) mud, normally deeply submerged, revealed abundant Callitriche palustris, colonies of mature plants with black fruits with many younger plants. A ‘guesstimate’ of the numbers was into the hundreds of thousands, and ‘a million’ was suggested!

It seems probable that the mud with the oldest, largest, plants was exposed only after the start of June. The long dry spell had then dried out these mudbanks creating extensive shrinkage fissures, visible in the photos. Many mature plants seemed rooted in the fissures, appearing as survivors of the earliest germination within the fissures during the dry period, perhaps due to better access to moisture below. With the return of damper weather, a new generation of seedlings was now apparent on the open surface of the mud, with shoots no longer than a centimetre or so. For a plant still regarded as rare in the country as a whole, the huge abundance of plants over a wide area was astounding. We now had the opportunity, and indeed luxury, to gain familiarity with this plant and its identification.

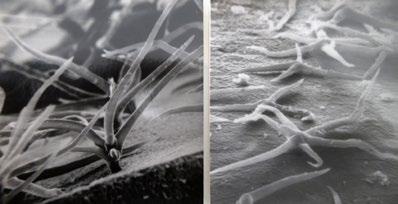

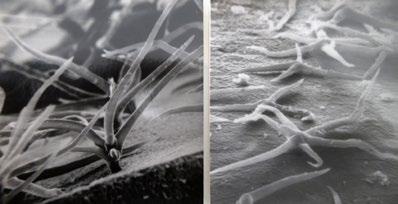

From the smaller quantities of C. brutia and C. stagnalis also present, C. palustris gave itself away at once with the abundance of fruits, many already breaking down to reveal the four black seeds inside. (On the dark mud, the tiny fruits a millimetre across could not be seen from standing. A disconcerting sight for anyone looking down from the access road would be the scatter of human forms, prostrate, or

BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023 19

Left: a Callitriche palustris shoot, with Lythrum portula Jeremy Roberts; right: Plant being held to show scale. Trevor Lowis

Callitriche palustris (Narrow-fruited Water-starwort): a Cumbrian annus mirabilis

Callitriche palustris (Narrow-fruited Water-starwort): a Cumbrian annus mirabilis

crawling apparently aimlessly on hands-and-knees, in that huge expanse of mud! I retain evidential photographs.)

Mature plants of C. palustris consisted of a congested and strongly rooted central portion, often several intertwined. Prostrate shoots emerged to a length of 3–8 cm. Nodes towards the base of these elongate shoots indicated successful fruiting and seeds already dispersed. The middle sections showed two, three, or more nodes with ripe and ripening black fruits and apically there was every gradation from green unripe fruits to flowers. In striking distinction, the longer shoots of C. brutia

plants showed no sign whatever of flowers or fruits developing on their outer portions, and the very few fruits observed were on the basal portions, often tucked down into the mud from the semiimmersed stems. (Fruits were more-or-less sessile, and the assumption is that these brutia plants are of subsp. hamulata, the typical Callitriche of Lake District waterbodies, distinctive enough when in its submerged form; subsp. brutia, distinguished by often longer peduncles, has yet to be recorded in Cumbria.)

Fruits provide immediate distinctions between C. palustris and other British and Irish species. The colour of the fruit is often given as a crucial feature – e.g. Stace (2019), ‘The black fruits (when fully ripe) are diagnostic’ – but note that Lansdown (2008, p. 22) lists C. brutia and some non-British species as having ‘black fruit’ when ripe. Two further features of the fruit are very useful: (i) its narrow dimensions (width slightly narrower than length) and somewhat ‘heart-shaped’ appearance from the side, and (ii) the almost complete lack of visible styles. Very short arching styles can rarely be seen on the very closest inspection, but generally are lacking. The other species at this site have long and more persistent styles, in C. stagnalis variously erect, arching or spreading, and in C. brutia strongly reflexed downwards, hugging the sides of the fruit (indeed often emerging sideways from the upper portion of fruits, with rows of cells above the point of emergence).

The jet-black colour of the fruits is in reality the colour of the four seeds within. To follow Lansdown’s (2008) explanation, the fruit is a schizocarp, and has a thin and translucent outer coat, which disintegrates with the maturation of the four mericarps containing the seeds. It is the rim of the mericarp which forms the translucent so-called ‘wing’, which provides significant characters. In C. palustris a wing is wellmarked around the apical half of the mericarp, but absent towards the base (in our form). In brutia and stagnalis, the wing is present right around the structure.

A very obvious feature of C. palustris at Haweswater was that the long fruiting stems had sparse, or no,

20 BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023

Top: Callitriche palustris shoot with ripe and unripe fruits; bottom: distinctive black appearance of the fruits due to the dark seeds showing through the translucent mericarp. Jeremy Roberts

development of nodal roots along their length, so that – very handily – a shoot could be grasped by its tip and then lifted away almost to its base. This very ‘open’, spreading and loose growth of C. palustris was in marked contrast to the dense and mat-forming patches of C. brutia, clinging firmly to the mud. C. brutia nodal root development was far greater: pulling at a shoot tip merely caused the stem to fracture before the first node down, and so on downwards. To extricate a shoot of C. brutia intact required a blade below to sever the roots! At least at this site and in this season the vigorous fruiting on all longer shoots in C. palustris, compared to the sparse fruiting but strong vegetative mat-forming growth in C. brutia, suggest contrasting annual, versus perennial, strategies.

Leaves of C. palustris towards the base of shoots were lingulate, linear or narrowly expanded, and often distinctively deflexed, whilst more apical internodes had leaves slightly broader. No truly spathulate leaves were observed. The fresh apical growth of mature plants was a mid-green colour, but at this late stage of the season many leaves and some whole stems were ageing to yellow, making the plants very conspicuous. C. brutia had leaves of similar shapes, but remaining a deep green throughout.

Continuing down towards the water-line revealed smaller and less-developed plants. However, beyond the last plants of this and other species there was some hundreds of metres of recently-exposed bare mud, supporting the notion that this generation of plants resulted from seeds germinating after retreat of the water, i.e. ‘terrestrially’, and not from plants initially developing underwater and only exposed with water retreat.

The huge numbers of fruit on offer suggested collection of seed for the Millennium Seed Bank (MSB). Cloth bags were sent by them, and permission from owners United Utilities obtained, and on 16 September a crack team assembled, and Phill, Trevor Lowis, Gary Lawrence and myself spent an entertaining couple of hours collecting shoots. Each shoot required scrutiny with pocket lens to ensure its identity. After partial drying on tissues overnight prior to posting, it was reassuring to see

how very many seeds were already shed. The final total is likely to be into the thousands. We await feedback from MSB as to how the collection fared in curation, but the haul will be satisfyingly above the ‘147’ seeds sent in 2016!

Using various sources, the area of mud supporting Callitriche palustris was estimated to be at least 150 × 270 metres, or 40,000+ square metres. Over the whole site, an average of only 25 plants per square metre would thus provide a million plants. Substantial plants in some typical areas were counted in a random sample of five one-squaremetre quadrats, to suggest a population density in the region of 100–200 per square metre. (The photograph below of a particularly dense patch covers close to a third of a square metre of habitat. Using the software ImageJ to help count the plants of all sizes in the image revealed roughly 120 – a density of c. 350 plants per square metre!)

A further visit by the author on 26 September allowed time for investigation into the plant communities. The main colonies of Callitriche palustris were in communities seeming to match closely the National Vegetation Classification OV31, the ‘Rorippa palustris-Filaginella uliginosa community’ of Rodwell (2000) – with the Rorippa being here represented by R. islandica (Northern Yellow-cress) in quantity, and Filaginella (Gnaphalium) uliginosum

BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023 21

Dense patch of c. 120 plants of Callitriche palustris with OV31 associates. Jeremy Roberts

Callitriche palustris (Narrow-fruited Water-starwort): a Cumbrian annus mirabilis

(Marsh Cudweed) in overwhelming abundance, with small but already-fruiting plants. Other associates typical of this association and abundant were the knotweeds Polygonum depressum (= P. arenastrum; Equalleaved Knotgrass), Persicaria hydropiper (Water-pepper) and P. maculosa (Redshank). The much more local P. minor (Small Water-pepper) was another frequent associate. Lythrum portula (Water-purslane) was codominant in many areas and most attractive in its vinous flowers and flushing. Rodwell adds that ‘this community can provide a locus for the nationally rare Limosella aquatica’ – the delightful Mudwort, which was indeed present, but scattered and hardly yet flowering at that date. Juncus bufonius (Toad Rush) and Poa annua (Annual Meadow-grass) were other species of the OV31 community present in quantity.

It is reassuring to know that Callitriche palustris is well established in the muddy seed bank at Haweswater and may emerge and prosper in future years – when conditions suit. Richard Lansdown remarked (pers. comm.), ‘… we will never entirely

understand and certainly never be able to predict the fluctuations in populations of mud plants; species such as Callitriche palustris and (particularly) Limosella aquatica show massive population fluctuations, often with only a few hints as to why’. Rodwell (2000, p. 432) comments in similar vein, ‘Typically, like the commoner species in this community [OV31], populations of Limosella can vary greatly in size from year to year in any one place. The characteristic habitats here are not only unstable but quite often not precisely congenial for colonisation by a particular species’.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to John Poland for initiating the search in the first place; John, Phill Brown, Gary Lawrence and Trevor Lowis for sharing the tasks, and offering the sage comments that I anticipate from these gentlemen in discussions on the day and over an earlier draft; Richard Lansdown, referee for Callitriche, for several exchanges over the find and

22 BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023

Callitriche palustris (Narrow-fruited Water-starwort): a Cumbrian annus mirabilis

Seed collectors Phill, Jeremy and Gary, and the Callitriche habitat. Trevor Lowis

Two early records of the rare Rumex rupestris (Shore Dock)

the draft of this article; and John Gorst, ecologist at United Utilities, for permissions and other support.

References

Brown, P.L. & Roberts, F.J. 2017. Callitriche palustris (Narrowfruited Water-starwort) in Westmorland (v.c. 69), new to England. BSBI News 135: 38–39.

Lansdown, R.V. 2008. B.S.B.I. Handbook No. 11: Waterstarworts (Callitriche) of Europe. Botanical Society of the Britain Isles, London.

Rodwell, J.S. (ed) 2000. British Plant Communities, Vol. 5: Maritime Communities and Vegetation of Open Habitats. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Stace, C.A. 2019. New Flora of the British Isles (4th edn). C & M Floristics, Middlewood Green, Suffolk.

United Utilities: website ‘Haweswater Reservoir Monitoring Station’: riverlevels.uk/haweswater-reservoir-bampton#google_ vignette (accessed 6 October 2022).

Jeremy Roberts

Eden Croft, 2 Wetheral Pasture, Carlisle, CA4 8HU fjr@edencroft2.co.uk

DAVID PEARMAN

Someyears ago I came across a paper by the then Curator of the Herbarium in Edinburgh, Mr F.M. Webb (Webb, 1879). In this note he wrote: ‘Rumex rupestris . For an account of this as a British plant see Journal of Botany xiii, pp. 294, 337, and xiv, p.1, with plate. It was first noticed in Jersey by Rev. W.W. Newbould in 1841 [seemingly an error for 1842], but passed almost out of sight until studied and determined by Mr Briggs to be a plant of the Plymouth coast in 1875. I recognised in our collections two sheets each with one good specimen of the plant gathered by Professor Balfour at Babbacombe, 26th Aug. 1839 (one is marked “near Exeter, 1839”, that being his headquarters).’

I was finally able to visit the Herbarium in March 2022, and found the two sheets. They had good fruit, and I was sure that they were this species. I showed the scans to colleagues in Cornwall and Devon, Ian Bennallick and Andy Byfield, and they concurred. The characteristic large tubercles on all three tepals are clearly visible. Professor J.H.

Balfour

Rumex rupestris (Shore Dock) in typical habitat at Molunan, Mevagissey, E. Cornwall (v.c. 2), September 2017. Ian Bennallick

BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023 23

Two early records of the rare Rumex rupestris (Shore Dock)

(1808–1884) was Regius Keeper of the Herbarium at Edinburgh, the Queen’s Botanist at Edinburgh from 1845–1879 and founded the Botanical Society of Edinburgh in 1836.

These specimens are very interesting because the earliest record previously known for England, was 1859, from Three Cliffs Bay, Glamorgan; it also predates the discovery in Jersey in 1842 (Pearman, 2017) which itself was not clarified until 1876 (Trimen, 1876). Nineteenth century botanists

struggled in identifying this species, and to be fair, many current botanists do too.

However, there is a further conundrum. There are old records from east of Exeter, from Lyme Regis and Ringstead in Dorset, though personally I have reservations about some of those, and none have persisted. Other than these the furthest east that R. rupestris has ever been recorded in Britain is from Slapton Ley, about 18 miles to the west of Babbacombe. Initially I worried about this, but bearing in mind the above-mentioned difficulties of identification, I do not consider this a problem. I assume that there would have been plenty of suitable habitat around Babbacombe at that time.

This is yet another justification for the retention and use of herbarium specimens.

References

Pearman, D. 2017. The Discovery of the Native Flora of Britain & Ireland. Botanical Society of Britain & Ireland, Bristol.

Trimen, H. 1877. Rumex rupestris Le Gall. as a British plant. Journal of Botany 14: 1–4.

Webb, F.M. 1879. Notes upon some plants in the British Herbarium at the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh. Transactions and Proceedings of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh 13: 88–114.

David Pearman

Algiers, Feock, Truro TR3 6RA

dpearman4@gmail.com

24 BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023

The specimen of Rumex rupestris (Shore Dock) in the Edinburgh Herbarium. The label reads ‘Ex Herb. T. H. Balfour, Rumex rupestris, LeGall. Babbicombe [sic] Aug. 26. 1839’

Two early records of the rare Rumex rupestris (Shore Dock)

MICHAEL BRAITHWAITE

History

Pyrola minor (Common Wintergreen) was first reported in Berwickshire in Dr George Johnston’s Flora of 1831 where five localities were listed. It was recorded assiduously over the remainder of the nineteenth century, being among the most soughtafter species along with the scarcer orchids. Botanical recording was at a low ebb for the first half of the twentieth century, but has since achieved almost complete coverage of habitats likely to hold Pyrola

I first recorded Pyrola in Berwickshire in 1979, and thus have 40 years’ experience of the species. After some years’ experience of searching for historical localities, along with more general fieldwork, it became clear that the majority of the nineteenthcentury localities had been lost but that I was finding new localities, often in places where nineteenthcentury records could have been expected in view of the other early records from the localities in question.

Few of the nineteenth-century records were made in ancient woodland, reflecting the rarity of ancient woodland in the vice-county. Most were made in plantations and avenues where much of the planting dated from 1780 to 1820. There had clearly been active colonisation of Pyrola in the early part of the nineteenth century.

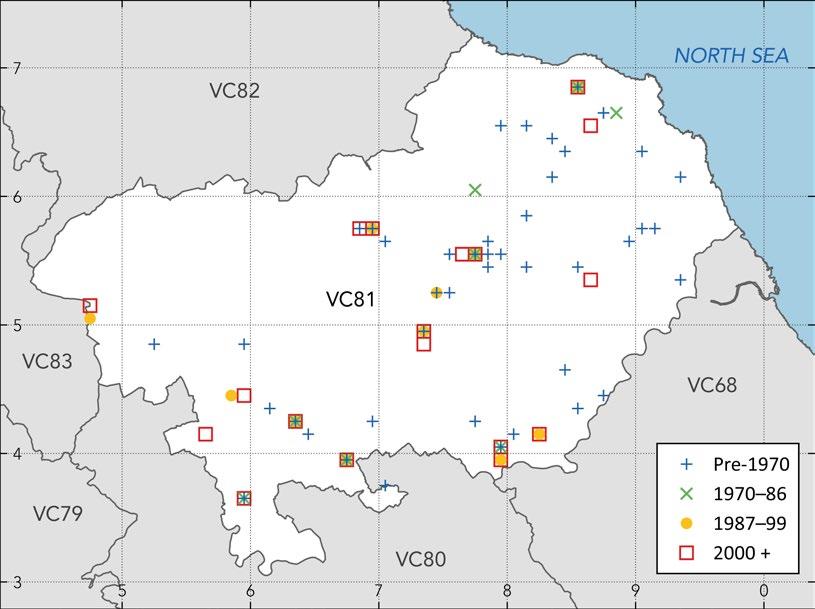

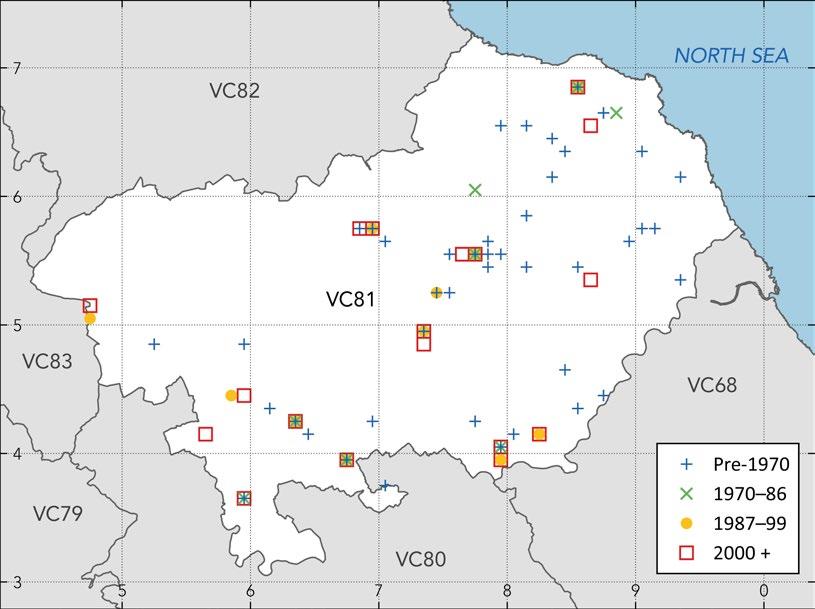

A number of my records, and those of other contemporary recorders, were made in mosses (mires). No nineteenth-century records were made in mosses, though one from ‘[moorland] near Dowlaw Dean’ probably relates to Long Moss, Coldingham Common NT86, where there had been extensive peat cutting followed by colonisation by birch and willow and where Pyrola still grows. Records are mapped in Figure 1.

BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023 25

Pyrola minor (Common Wintergreen), Green Ride, Marchmont (NT7348), on a bank under Fagus sylvatica (Beech), 15 June 2021. Robin Cowe

Modelling the history of Pyrola minor (Common Wintergreen) over 200 years in Berwickshire (v.c. 81)

Modelling the history of Pyrola minor (Common Wintergreen) over 200 years in Berwickshire (v.c. 81)

26 BSBI NEWS 152 | January 2023

Figure 1. Map showing the monad distribution of Pyrola minor in Berwickshire (v.c. 81)

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 1830 1850 1870 1890 1910 1930 1950 1970 1990 2010 Populations Ancient woodland

Figure 2. Graph showing the change over time in habitat preference of Pyrola minor in Berwickshire (v.c. 81)

Mosses Plantations Scrub

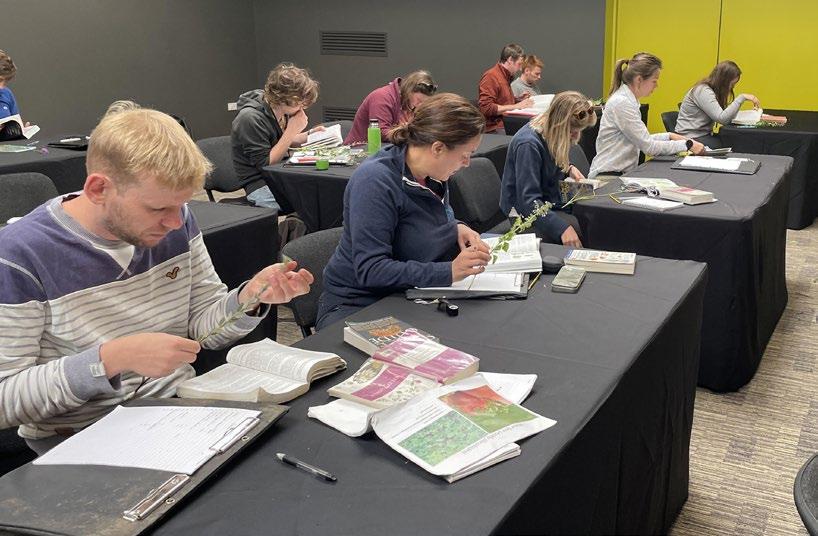

Habitat