This is from the catalog of Andre Brian a nursery in France as once again this particular variety is not very common in the trade here.

Another Choice Plant From Jimi Blake’s NPA Seattle Study Weekend Presentation

‘El Rayo’, in english is, ‘Lightning’! One should expect something pretty spectacular, flashy even, with this plant…or not. ‘El Rayo’ in Portland is a taqueria!…in Portland, ME that is. I would hope that the name of either doesn’t over sell their product! Does anybody know? About the tacos I mean? Gardeners should always be wary of cultivar names. While they serve as identifiers of a particular, and allegedly unique form or clone, and sometimes as a helpful and memorable descriptor, they can too often tread across the line into misleading hyperbole! Names are often assigned to a plant that have been in the trade for some time under other names. These ‘new’ and unique names are then ‘trademarked’, legally protected, as the nursery heavily markets the plant. The gardening public then comes to recognize and associate this protected name with the plant and begin to ask for it by that name. Unlicensed growers cannot supply the plant by that name and so some nursery producers carve out a larger share of the market. After experience we may come to recognize these marketing ploys…or not. Oft times a little celebration or indulgence is called for.

Anisodontea is a genus which includes 19-21 species, the total is not settled, all of them endemic to South Africa. It’s a member of the family Malvaceae which includes 243 genera and 4,225 species worldwide; 31 genera and 401 species of these are native to South Africa, a further eight genera and 20 species are naturalized there. Most gardeners, and many non-gardeners, know the Hollyhock, perhaps the most recognized Mallow, at least in the temperate north, a low care plant, if you can accept the rust here, a resident in many old flower gardens, Grandma gardens, and I don’t mean any slight here. Hollyhocks produced the little ‘buttons’ remembered by many of those in my generation as they played in gardens. What? Take a look at the little button-like pods that form after flowering. Other family members include the genus Hibiscus, which gardeners and non-gardeners commonly associate with exotic tropical locales even though there are many hardy North American species, some of which, they and their hybrids, are long serving constituents of cooler temperate gardens.

Lavatera, another familial genus, have been commonly used in many herbaceous, mixed and sometimes xeric, borders for years. It’s a genus of 25 species, found exclusively in the northern hemisphere, the Holarctic Floral Kingdom and one random member in Australia. It formed in an act of adaptive evolution paralleling the Anisodontea in South Africa’s Cape Floristic Region. The two genera are the products of two, discontinuous, genetic lines. Other typical garden plants of the family, like Sidalceae ‘Elsie Heugh’, have found space in many gardens, sometimes with their regional native ‘cousins’ here in Oregon, including S. virgata, S. campestris, S. nelsoniana, S. oregana and S. cusickii. Other gardeners grow lesser known western natives in their dry garden including the Sphaeralcea spp. and their few cultivars. There are even native desert species of Hibiscus found in the SW corner of North America. I’ve grown some of these, but have yet to try Anisodontea. Cotton, Okra and the iconic African ‘tree’, the Baobab, the world’s largest succulent, are also family members.

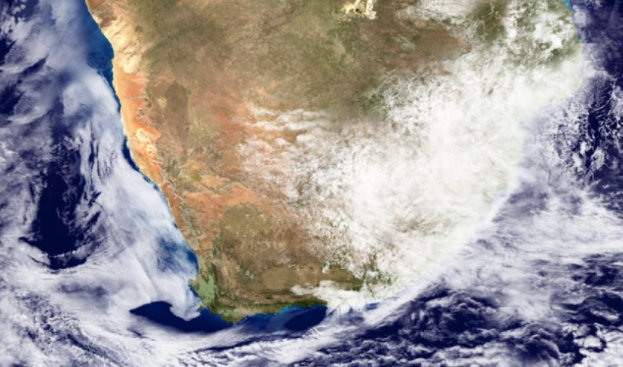

This satellite shot shows how the trade winds tend to bring ocean moisture to South Africa from the east moving westerly leaving the Region wetter in the east and drier in the west, which has a summer/dry, winter/wet climate much like the west coasts of the major continents around the world.

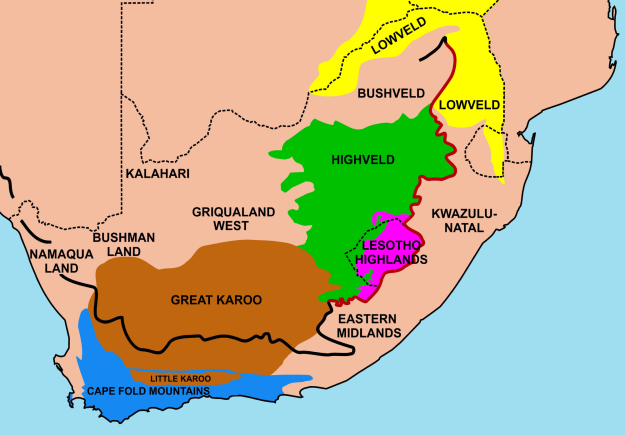

The southern end of the continent of Africa shows evidence of where it was torn away, in a ‘rifting’ process, that separated it from Antarctica many millions of years ago as the ‘super continent’, Gondwana, broke up. The Cape Fold Mountains, that parallel this rift, and the adjacent narrow coastal plain, contain rock that shares a common origination with the matching section of Antarctica. The high, dry plateau of the Karoo and High Veld, lie to the north and east, separated by the wall of the Great Escarpment. This remanent edge is the area that contains South Africa’s unique Fynbos plant communites with their many sclerophyllous, evergreen, shrubs, similar in appearance to California’s chaparral while being comprised of very different and often endemic species, many Ericaceous, Proteaceous and a significant portion of the world’s Restionaceae species, among others. Its climate is summer/dry, winter/wet with a moderating coastal influence. Anisodontea spp. grow in a narrow band along this part of the country, a band that widens as it swings east and north.

To this area’s east, beneath the heavy cloud cover shown in the above picture, are the East Cape and KwaZulu-Natal which have a summer, sub-tropical, wet season. Moving north from there, towards Johannesburg, Pretoria and into the Low Veld, the precipitation pattern becomes more pronounced, while being more humid and warm as one would expect in a sub-tropical region. The summer/wet pattern is fed by the summer oscillation of the InterTropical Convergence Zone, the ITCZ, as it shifts southerly during the southern hemisphere’s summer…but this ‘wet season’ can vary widely in its impact from year to year depending on how far south the oscillation reaches. Some years the Trade Winds, the south-easterlies, off of the Indian Ocean, and the westerlies, blowing across the colder ocean to the south, remain a more dominant factor. It is always the marginal areas that experience the greatest variations. The ITCZ is a major factor around the globe driving and influencing all of its weather. In Africa, as you move north from here, into Central Africa, the ITCZ has a much larger and consistent impact on the weather and rainfall amounts. (If you have the time, and interest, check out this site periodically to see what the weather is doing there in real time. This site is useful for the weather patterns anywhere on Earth.) As the season moves away from summer, and the oscillation, this area falls back under the influence of the ‘returned’ southeasterly trade winds off of the relatively warm Indian Ocean. This ‘local’ maritime pattern results, in a more humid and moderate pattern than the interior and SW parts of the country which are influenced more by the colder/drier waters south toward Antarctica. The country, overall, has complex weather, a pattern that I’m sure I’m not getting quite right. Needless to say, it is very different than ours in the PNW!

The South African endemic Anisodontea spp. are not well known here in the states, at least in the more mid-temperate regions north of California. These range inland along almost the entirety of South Africa’s coast, just into the dry Karoo where it abuts mountains, absent through out the dry interior north of the ‘Great Escarpment’ and the high, dry plateau of the central part of the country. The Karoo covers much of central South Africa west of the Drakensburg Mountains and north of the Little Karoo and the ancient Fold Mountains to the south. The mountains tend to block and steer precipitation from the bordering oceans and it is in these more coastal, wetter, areas where the species A. capensis is most likely to be found. In Britain the RHS suggests that this is drought tolerant, and it may well be in their maritime influenced, wetter summer climate, but for us in the summer dry west coast of North America it will likely require at least some summer water to help it perform.

Important geographical regions in South Africa. The thick line traces the course of the Great Escarpment which edges the central plateau. The eastern portion of this line, coloured red, is known as the Drakensberg. The Escarpment rises to its highest point, at over 3000 m, where the Drakensberg forms the border between KwaZulu-Natal and Lesotho. None of the regions indicated on the map have sharp well-defined borders, except where the Escarpment, or a range of mountains forms a clear dividing line between two regions. Some of the better known regions are coloured in; the others are simply indicated by their names, as they would in an atlas. [from Wikipedia]

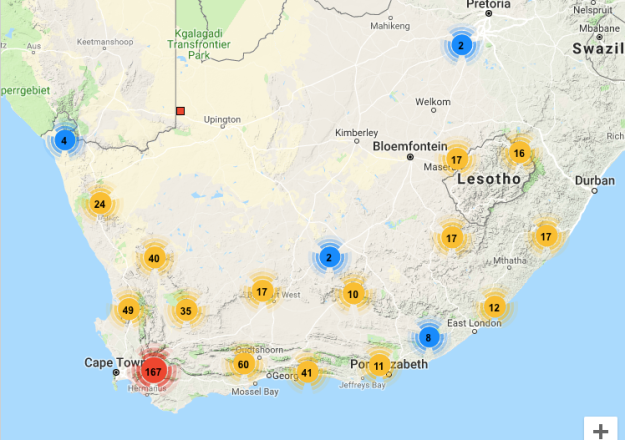

This map, taken from the SABI website, shows the distribution of Anisodontea capensis. It tends to avoid the driest portions of the interior Karoo and High Veld as well as the far NE area above Durban. I’ve written before that plants are my way of exploring the world and its geography. To understand a plant one needs to understand where it came from in its broadest most inclusive sense. To grow it successfully one must also understand ones on garden and the region of which it is a cohesive part.

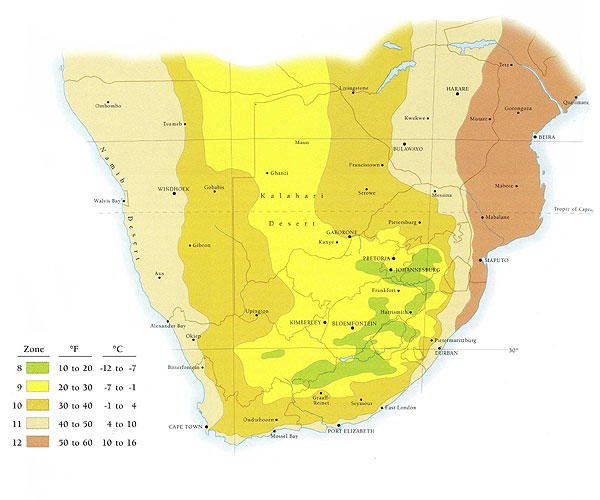

This map reflects the USDA designated growing zones applied to South Africa. As with any such map this cannot show every cold spot as these vary widely with the land forms. The warmer east coast temperatures are reflective of the warmer Indian Ocean, while the cooler and drier west coast results in large part to the wind patterns coming off of the colder ocean to the south which carries less water vapor. The colder temps in the middle are reflective of their position at some remove from the Oceans and their overall higher elevations. Recall that the High Veld sits atop the plateau of the Great Escarpment which was once capped with many feet of basalt, most of which has eroded away.

The South African Biodiversity Institute, the SABI, has produced another growing zone map based on the seasonality of rainfall. I include a link here as it is helpful when trying to visualize growing conditions, however, you must realize that the amounts that fall during those periods are not reflected in the color coded map. One area may receive little if any rainfall in the average summer while another may receive much heavier and consistent amounts. They share the same color designation simply because the receive most of their rain during the same period. The summer rainfall areas are all strongly influenced by the previously discussed ITCZ.

As a native in sub-tropical South Africa and restricted to low-moderate elevations, we shouldn’t expect this to be very cold hardy. Some growers rate it to the equivalent of our zn 9a, or down to 20ºF. The Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) recommends it for sheltered sites in the UK and give it an H2 rating, equivalent to a cool/frost-free greenhouse. For them an H3 rating covers most of coastal and the milder parts of Britain having a rating equivalent to our USDA zn 9b/10a with a minimum temperature of 1ºC to -5ºC or 33ºF – 23ºF. Much of Britain is covered by their H4 zone, equivalent to our 8b/9a. Its most severe pockets in the north they rate at H-6. I like this handy and descriptive chart of their rating system. Once again they are much more ‘civilized’ than us Yanks!

Lavatera spp. and Anisodontea spp. are similar in habit and morphology though many Lavatera are coarser in texture, with bigger leaves and flowers and are hairier, fuzzier over all, a common adaptation of plants in more arid climates as this tends to reduce a plant’s use of water. Anisodontea spp. have similarly softly lobbed leaves. A. capensis ‘El Rayo’ grows to about 3′ tall x 2 1/2′ wide. It has bright pink flowers with a darker, more purple, ‘eye’ while the species can range from near white to much darker. Each flower carries five petals surrounding a combined stamen/style, fused into a tube, projecting out above the ovary, a structure that is common in the family…think classic Hibiscus flower, about 2″ across, blooming May through October in milder climes, though they are capable of flowering year round if mild enough.

This a picture of Anisodontea ‘Tara’s Pink’ from my friend’s blog at Gardening with Grace. It’s flowers have more of a distinct bicolor toned pink in addition to being a taller plant and is said to be hardy to zn8. It’s flowers have a more distinct bicolor toned pink in addition to being a taller plant that. Down in Albany, Grace, like many of us too often do, didn’t get this one in the ground to establish before winter…and it failed to survive the winter of ’15-’16 there. It wasn’t really a fair test.

‘El Rayo’ isn’t readily available around the PNW, but a few nurseries in California, like Devil Mountain, list it, though you would have to go to one of their stores in the Bay Area to buy it. ‘El Rayo’ is again, more commonly offered in Europe. Some US nurseries claim that what is sold as A. capensis here is actually A. x hypomandarum, a synonym according to botanists in South Africa…hmmm. San Marcos Growers, a larger wholesale grower in California, is one of those and claim that Anisodontea are very promiscuous. Sorting out the genetics of this will require the focused attention of a lab…which probably won’t happen. San Marcos doesn’t offer ‘El Rayo’, but they do list a couple other species and the hybrids, ‘Tara’s Pink’ and ‘Tara’s Wonder’, two crosses utilizing other species and, they say, A. x hypomandarum, that contribute a little more cold hardiness in addition to effecting the leaves, flowers and height. These are taller plants, 5′-8′. Native Sons, another California wholesale nursery offers ‘Tara’s Wonder’ which they describe as growing to 5′-6′. The Tara hybrids were found at San Marcos where they arose spontaneously as seedlings. Other sellers are offering the Tara series of hybrids as selections of A x hypomandarum alone adding further confusion. More locally, Blooming Advantage offers A. hypomandarum ‘Tara’s Pink’, without the ‘x’ in the name that denotes it as a hybrid. This ‘looseness’, which sometimes occurs in the industry, tends to confuse the naming and identification of plants. This is why Botanical gardens go to great effort with their accessions…they need to know a plant’s provenance, who it was acquired through and where, specifically, it came from. It is easy to lose this thread.

All of this aside, this is a fine plant!