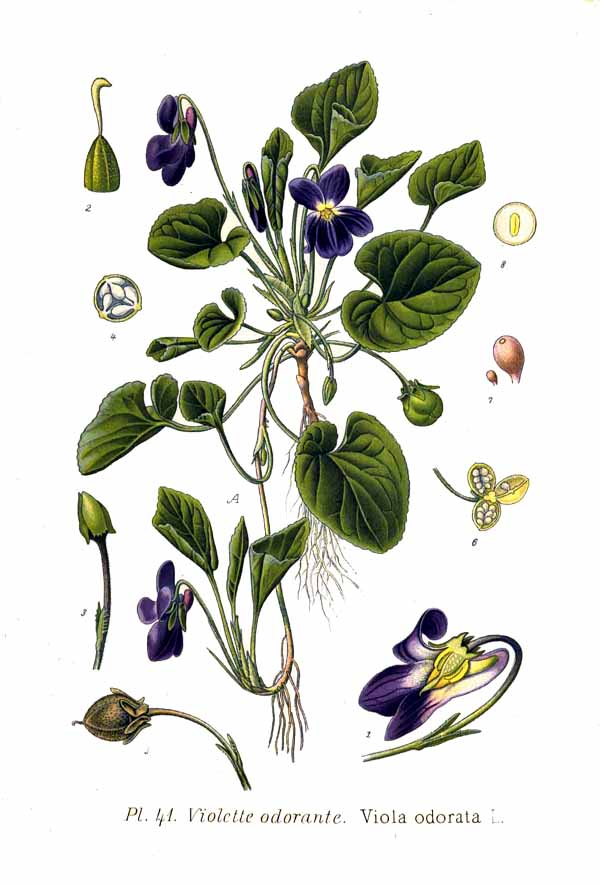

Viola odorata, painting by Amédée Masclef – Atlas des plantes de France. 1891, Public Domain, Wikipedia. Note that the main plant has a runner (stolon) which has formed roots and sprouted a daughter plant. Also note that flowers can be white/pink/apricot.

Some flowers provide inspiration for poets and artists. Violets certainly do this, and (unusually for me) I’m starting this article with a poem about them, written over 200 years ago.

Jane Taylor (1783-1824) was an English poet best known for writing the lyrics of Twinkle Twinkle Little Star. One of her lesser known poems is about violets:

Her flower must have been Viola odorata as the other species of Viola are scentless. It was first described as Viola purpurea by the Yorkshire botanist Thomas Johnson in 1629. It is common and native in England but rather rare in Scotland although probably still native. We know that it has existed in Scotland for a while: the Scottish poet James Hogg (1770 – 1835, known as ’the Ettrick Shepherd’) wrote a poem about the plant at the same time as Jane Taylor’s (it was the Romantic Period, an age of flower-poems). Also, it is recorded in W. J. Hooker’s Flora Scotica of 1821. In recent decades it has declined in the western parts of Scotland- see the BSBI distribution map (at the end of this article).

Sweet Violet in the wild area of a garden, along with Primula vulgaris. Photo: John Grace

It grows on calcareous and base-rich soils, in woodlands, hedges, banks and verges. There are many garden forms which have become naturalised. The plant has a rich folk-history. In olden times the flowers were strewn on the floors of dwellings to sweeten the air.

The family Violaceae contains violets and pansies. They may be annuals or perennials but most are perennials. The flowers of violas come from a basal rosette, a feature which somewhat limits the size of the plant. Their flowers are unusual: there are five petals but the lower one has a backwardly directed spur which contains two of the five stamens.

Sweet Violet, detail of flower. The downward-directed hairs on the petiole are visible on the right-hand image. Photo: John Grace

How can the botanist be sure of identification? There are several other common violets1. But V. odorata is the only one that is scented, has runners (stolons), and very short backwardly directed hairs on the flower- and leaf- stalks (they are less than 0.5 mm and a hand lens is usually needed to see them). The scent maybe faint in cold weather; but if a flower is placed in a closed pot and brought into the warm indoors, opening the lid will release the pleasing volatile compounds (they are complex ketones known as ionones, and used in perfumes and confectionaries).

Detail of leaf, both surfaces, with enlarged view of leaf base to show hairs. These are winter leaves. Those formed in summer are usually more pointed. Images: John Grace

The genus Viola has engaged the interest of several generations of botanists. Eliza Gregory (1840-1932) was an English botanist who published a comprehensive monograph on Viola in 1912 where she described 12 British species2. Now, in Stace (2019) her original 12 species have been reduced to seven; moreover, Stace does not list the distinct variety3 of V. odorata that she discovered: V. odorata var. praecox, Gregory. In 1912 she wrote

“A plant differing from the type V. odorata in its smaller and darker, though equally fragrant flowers, in its more slender stolons and somewhat smaller spring leaves, has been noticed by me for many years. A careful study of the plant in all its stages induces me to believe it to be quite worthy of varietal rank, and I propose to add it to our flora under the name V. odorata var. praecox”.

Stolons grow from Sweet Violet plants. They bear ‘daughter’ plants and thus the violet patch expands. Photo: John Grace.

She continues with a detailed description and illustrations of the leaves. The particular interest in this variety is that it starts flowering very early, in deepest winter and may have flowers all the year round (‘praecox’ means precocious). I noticed flowers on the violet in my garden in early January – it may have been flowering before I saw it. There are only a few insects around at this time, and the scent is weak at low temperatures, so I wonder why the precocious trait has evolved.

When I started this blog I had not realised that Viola species are partially cleistogamous, i.e. the flowers remain closed but self-pollination takes place nevertheless, ‘behind closed doors’. In 1929 Margaret Madge, working at what was then called the Studley Horticultural & Agricultural College for Women, published an interesting paper describing her close observations on V. odorata var. praecox growing at the Royal Holloway College in London. She found that it was cleistogamous in the summer months (from May to September) but had open or partially open flowers for the rest of the year. Seeds can be formed irrespective of whether the flowers are open or closed but, remarkably, cleistogamous flowers yield the majority of seed. Yet is nevertheless hard to see why the flowers should be closed in summer, when insects are abundant and cross pollination might be expected to be more useful than cleistogamous selfing. Water economy may have been a factor in the evolutionary past: flowers of all species have stomata and so having closed flowers may reduce water use and be a response to a dry climate.

V. odorata growing in the wild, Drum Wood, Edinburgh. Photo: Sue Jury.

Several insect groups have been observed to visit violets for both nectar and pollen: Beattie (1972) recorded Solitary Bees, Bumblebees, Hoverflies and Bee-flies. He examined stomach contents and found violet pollen but also other pollen types. Many had dandelion pollen. He makes the point that food is scarce when insects first emerge in the spring and those species which open their flowers early may therefore have a high chance of cross-pollination.

As with quite many small herbaceous perennials, the seeds of Viola are dispersed by ants. Seeds are yellow–brown and they have a paler, nutritious and lipid-rich appendage called the elaiosome which ants want to eat. The ants harvest the seeds and carry them back to their nests. They share the elaiosome with nest-mates and then discard the seed, away from the nest and sometimes in a good spot for germination.

Seeds of Viola elatior with their pale elaiosomes. Credit: Hans Stuessi, CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

I searched the Web of Science to find examples of modern research on Viola odorata. There is much on the pharmacology – Sweet Violet has been an important component of Herbal Medicine since the early times. Gerard’s Herbal of 1597 records many uses and so it is interesting to see what sorts of modern medicine might be made from it. Extracts are being tested for a wide range of conditions including cancer, Alzheimer’s Disease, insomnia and Covid-19. As an occasional insomniac, I was especially interested to see that nasal drops made from Viola may help older adults to sleep well.

Of particular interest are several well-cited titles about a class of chemicals called cyclotides. These are peptides found in only a few plant families (including Rubiaceae, Violaceae, Cucurbitaceae). They have remarkable and diverse biological properties which are only now being discovered. Some have a potent insecticidal activity, others are useful in childbirth.

Sometimes new research verges on ‘beyond belief’. In a 2018 article from Tehran, I learn that oil extracted from seeds of Viola odorata may be a valuable diesel fuel. I’m trying to imagine how many cleistogamous violets would need to be grown, irrigated and processed for me to drive from Edinburgh to Glasgow. Quite a lot.

A Little Violet Seller 1877. Augustus Edwin Mulready, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In Victorian London, street urchins would sell bunches of Sweet Violets, as recalled in the music-hall song ‘Won’t you buy my pretty flowers’. Here is a quote from the Dictionary of Victorian London. The interviewer asks a Flower Girl what she sells:

“I sell flowers, sir; we live almost on flowers when they are to be got. I sell, and so does my sister, all kinds, but it’s very little use offering any that’s not sweet. I think it’s the sweetness as sells them. I sell primroses, when they’re in, and violets, and wall-flowers, and stocks, and roses of different sorts, and pinks, and carnations, and mixed flowers, and lilies of the valley, and green lavender, and mignonette (but that I do very seldom), and violets again at this time of the year, for we get them both in spring and winter.”

The last few words are of botanical interest. She doesn’t sell them in the summer because that’s when they are cleistogamous.

Distribution of Viola odorata. Note the paler squares where the species has not been recorded in recent decades. Map: BSBI.

Notes

1other species are Common dog violet Viola riviniana, Early dog violet Viola reichenbachiana, Heath dog violet Viola canina, Pale dog violet Viola lactea, Fen violet Viola persicifolia, Hairy violet Viola hirta, Marsh violet Viola palustris, and Teesdale violet Viola rupestris. The best way to tell them apart is the key in Rich and Jermy’s Plant Crib; the violet section can be freely downloaded here.

2 as well as 12 Viola species she describes many forms and hybrids. Some appear to have been collected in the gardens of friends, suggesting they are horticultural strains in general circulation among gardeners of her time. Her complete monograph can be freely downloaded from the Wellcome Collection here.

3there are many recognised varieties of V. odorata and many can be viewed here. There are too many to be listed in any national Flora.

References

Beattie AJ (1972) The pollination ecology of Viola. 2, Pollen loads of insect-visitors. Watsonia, 9, 13-25.

Gregory ES (1912) British Violets, a monograph. Heffer, Cambridge. https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/pdf/b28099266

Madge AP (1929) Spermatogenesis and fertilisation in the cleistogamic flower of Viola odorata var. praecox. Annals of Botany 43, 546.

Servine P & Detrain C (2010) Opening myrmecochory’s black box: what happens inside the ant’s nest? Ecological Research 25, 663-672.

Stace CA (2019) New Flora of the British Isles, 4th edition. C&A Floristics.

I love violets, they make my heart melt

LikeLike

Every week I send you a mental thankyou.

LikeLike