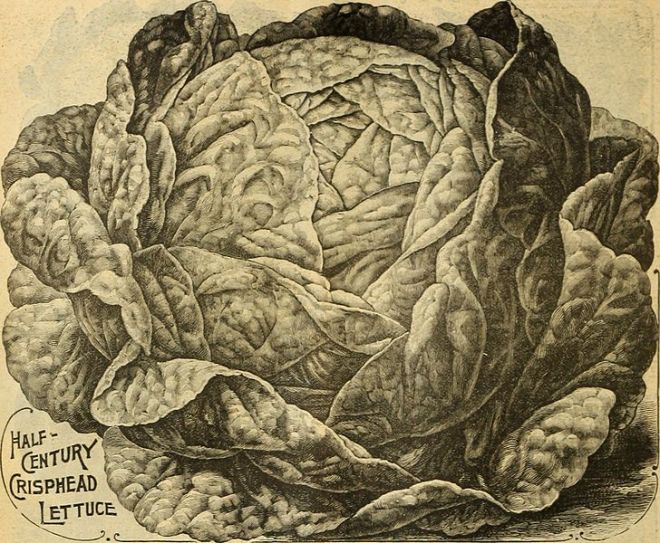

Lettuce, domesticated about six thousand years ago in a region referred to as the Fertile Crescent, bears little resemblance to its wild ancestors. Hundreds of years of cultivation and artificial selection eliminated spines from the leaves, reduced the latex content and bitter flavor, shortened stem internodes for a more compact, leafy plant, and increased seed size, among several other things. The resulting plant even has a different name, Lactuca sativa (in Latin, sativa means cultivated). However, cultivated lettuce remains closely related to its progenitors, with whom it can cross to produce wild-domestic hybrids. For this reason, there is great interest in the wild relatives of lettuce and the beneficial traits they offer.

image credit: wikimedia commons

Crop wild relatives are a hot topic these days. That’s because feeding a growing population in an increasingly globalized world with the threat of climate change looming requires creative strategies. Utilizing wild relatives of crops in breeding programs is a potential way to improve yields and address issues like pests and diseases, drought, and climate change. While this isn’t necessarily a new strategy, it is increasingly important as the loss of biodiversity around the globe threatens many crop wild relatives. Securing them now is imperative.

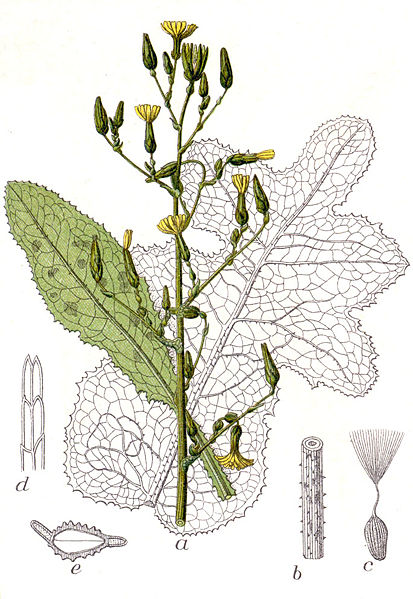

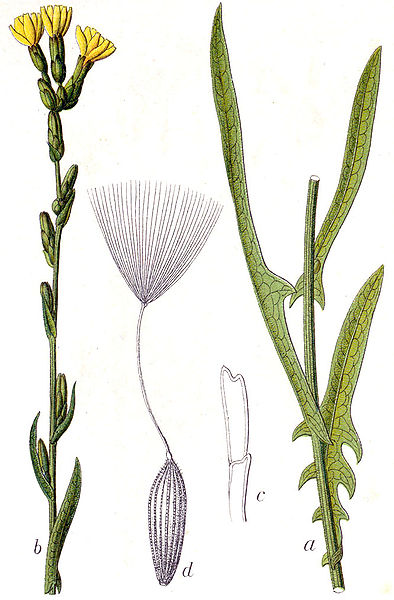

There are about 100 species in the genus Lactuca. Most of them are found in Asia and Africa, with the greatest diversity distributed across Southwest Asia and the Mediterranean Basin. The genus consists of annual, biennial, and perennial species, a few of which are shrubs or vines. Prickly lettuce (L. serriola), willowleaf lettuce (L. saligna), and bitter lettuce (L. virosa) are weedy species with a wide distribution outside of their native range. Prickly lettuce is particularly common in North America, occurring in the diverse habitats of urban areas, natural areas, and agricultural fields. It is also the species considered to be the main ancestor of today’s cultivated lettuce.

In a paper published in European Journal of Plant Pathology in 2014. Lebeda et al. discuss using wild relatives in lettuce breeding and list some of the known cultivars derived from crosses with wild species. They write that in the last thirty years, “significant progress has been made in germplasm enhancement and the introduction of novel traits in cultivated lettuce.” Traditionally, Lactuca serriola has been the primary source for novel traits, but breeders are increasingly looking to other species of wild lettuce.

bitter lettuce (Lactuca virosa) – image credit: wikimedia commons

Resistance to disease is one of the main aims of lettuce breeders. Resistance genes can be found among populations of cultivated lettuce, but as “extensive screening” for such genes leads to “diminishing returns in terms of new resistance,” breeders look to wild lettuce species as “sources of new beneficial alleles.” The problem is that there are large gaps in our knowledge when it comes to wild lettuce species and their interactions with pests and pathogens. Finding the genes we are looking for will require “screening large collections of well defined wild Lactuca germplasm.” But first we must develop such collections.

In a separate paper (published in Euphytica in 2009), Lebeda et al. discuss just how large the gaps in our understanding of the genus Lactuca are. Beginning with our present collections they found “serious taxonomic discrepancies” as well as significant redundancy and unnecessary duplicates in and among gene banks. They also pointed out that “over 90% of wild collections are represented by only three species” [the three weedy species named above], and they urged gene banks to “rapidly [acquire] lettuce progenitors and wild relatives from the probable center of origin of lettuce and from those areas with the highest genetic diversity of Lactuca species” as their potential for improving cultivated lettuce is too important to neglect.

Lactuca is a highly variable genus; species can differ substantially in their growth and phenology from individual to individual. Lebeda et al. write, “developmental stages of plants, as influenced through selective processes under the eco-geographic conditions where they evolved, can persist when plants are cultivated under common environmental conditions and may be fixed genetically.” For this reason it is important to collect numerous individuals of each species from across their entire range in order to obtain the broadest possible suite of traits to select from.

One such trait is root development and the related ability to access water and nutrients and tolerate drought. Through selection, cultivated lettuce has become a very shallow-rooted plant, reliant on regular irrigation and fertilizer applications. In an issue of Theoretical and Applied Genetics published in 2000, Johnson et al. demonstrate the potential that Lactuca serriola, with its deep taproot and ability to tolerate drought, has for developing lettuce cultivars that are more drought tolerant and more efficient at using soil nutrients.

willowleaf lettuce (Lactuca saligna) – image credit: wikimedia commons

Clearly we have long way to go in developing improved lettuce cultivars using wild relatives, but the potential is there. As Lebeda et al. write in the European Journal of Plant Pathology, “Lettuce is one of the main horticultural crops where a strategy of wild related germplasm exploitation and utilization in breeding programs is most commonly used with very high practical impact.”